Archive for the ‘Signal Integrity’ Category

To Know The Bit Error Rate Is To Know The Bit Error Ratio

Recently I came across a blog post titled, “Can Oscilloscopes Really Calculate BERs?”, written by Ransom Stephens.

I liked this article. I liked it because, as usual, Ransom likes to challenge your way of thinking and makes you go back to basics in order to understand. For example, when he debates whether BER is “bit error ratio” or “bit error rate”, it stopped me in my tracks to question if I was using the correct terminology, and why. For the record, when I started my career working on T1 line repeaters, I was taught it was “rate”. But, technically, Ransom’s assertion that it really is “ratio” is also correct.

Before you discount this and say, “In mathematics, there can be only one answer”, stay with me here, and let me try to explain where I’m coming from. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, the definition of ratio is, “the indicated quotient of two mathematical expressions”, or “the relationship in quantity, amount, or size between two or more things: proportion”. If you take the number of bit errors and divide them by the total number of bits, then you have, by definition, a ratio, as Ransom claims. For example, if you have 1 error in 1 TBits of data, then you have a “bit error ratio” of 1E-12.

When you look up the word rate, in the same dictionary, the definition is, “reckoned value: valuation” or “a fixed ratio between two things”. In terms of BER, when it is defined as rate, the fixed ratio between two things is the number of errors over some period of time. Since a bit has a time component associated with it, you can convert the total number of bits into time by multiplying it by the bit time. For example, at 10 GB/s, the bit time is 100 ps. So 1TB of data takes 100 seconds to transmit all of the bits. If there was 1 bit error during that time, you would have a “bit error rate” of 1 error per 100 seconds.

In mission critical applications, we usually aspire to have error-free performance for the life of the product. As bit rates continue to climb, that’s an awful lot of bits. Theoretically, if you want your product to have a bit error rate of 1 error in 25 yrs, then, at 10GB/s, you would need to transmit 7.884E+18 bits;[25yrs*(60*60*24*365)sec/yr*10GB/s] to have a bit error ratio of 1.268E-19!

Bit error ratio, or bit error rate? It kind of reminds me of part of the song, “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off”, by George and Ira Gershwin; “You like to-may-toes, and I like to-mah-toes”. At the end of the day, it’s still tomatoes. In the right context, I think both terms are equally valid. You need to be ambidextrous, so to speak, in your analysis and how you quote the number.

PCB Vias Are Capacitive But Not Necessarily Capacitors

Huh? …… What do you mean by that? ……

For years now the popular opinion was that PCB vias were capacitive in nature, and therefore could be modeled with lumped capacitors. Although this might be true when the rise time of the signal is greater than or equal to 3 times the delay of the via discontinuity, I’ll show you why it is no longer appropriate to think this way; even risky to continue to model your high-speed channel using this methodology.

Let’s start the discussion by saying vias are transmission lines with excess parasitic capacitance or inductance. Vias are considered transparent when their impedance equals the characteristic impedance of the transmission lines attached to them. In almost all cases, vias passing through multi-layer PCBs are capacitive because of the distributed capacitance between the via barrel and anti-pads. As a result, they end up having lower impedance than the traces connected to them. Like any other transmission line, when a rising edge of a signal encounters a lower impedance, it will cause a negative reflection for the length of the discontinuity.

Getting back to the point, it is best demonstrated by an example as summarized in Figure 1. Consider a via at the far end of a long 50 Ohm transmission line. The via has a short through section and a long stub section. The through section is 15 mils and the stub is 269 mils for a total via length of 284 mils. This is not unusual for modern backplane designs.

For this particular via geometry, the impedance is 33 Ohms and the excess via capacitance is 1.9pf. Even with a fast 50ps rise time at the source, by the time the signal reaches the via at the far end, the rise time will degrade due to dispersion caused by the lossy dielectric. In this example, after 23 inches, the rise time has degraded to approximately 230ps.

If the total delay (TD) of the via discontinuity is 60 ps, then the 230 ps rise time at the via is greater than 3TD (180ps). As expected, when modeling the via with a lumped capacitor equal to the excess capacitance, and comparing it with the transmission line via model, the TDR plot of the reflections are virtually the same using a 230ps rise time.

Figure 1 Via model TDR comparison after 23 inches. Top topology uses 33 Ohm transmission lines for both the through and stub portion of the via. The bottom topology models the via with a 50 Ohm transmission line to represent the delay of the through portion and a 1.9pf capacitor to represent the excess capacitance. Modeled and simulated with Agilent ADS.

So far so good, right? Well maybe so. The only way to know is to explore this topology even further and compare eye diagrams. Let us say your circuit needs to work at XAUI rate of 3.125 GB/s. You modify both topologies by adding a driver and receiver. After simulating you end up with eye diagrams as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Eye comparison at 3.125Gb/s. Top topology uses 33 Ohm transmission lines for both the through and stub portion of the via. The bottom topology models the via with a 50 Ohm transmission line to represent the delay of the through portion and a 1.9pf capacitor to represent the excess capacitance. Modeled and simulated with Agilent ADS.

Still ok. So what is your point, you might ask?

You are correct when you comment there is a good match for reflections and the eyes are wide open. Ah, but now let us say you want to run this at 10GB/s down the road. So you dial up the bit rate on the transmitters and simulate both topologies again. But this time, you get some unexpected results as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Eye comparison at 10Gb/s. Top topology uses 33 Ohm transmission lines for both the through and stub portion of the via. The bottom topology models the via with a 50 Ohm transmission line to represent the delay of the through portion and a 1.9pf capacitor to represent the excess capacitance. Modeled and simulated with Agilent ADS.

Ouch! What happened here? Looking at the TDR, the reflections at the end of the channel look the same so why doesn’t the receive eyes match? To answer this question, we really need to look at the S-parameter plots of both channels. Figure 4 shows the insertion and return losses of both topologies. Red is the transmission line model and the blue is the capacitor model.

Figure 4 Insertion and return loss of both topologies. Red curves are the transmission line via model and blue curves are the capacitor model.

The insertion loss plot represents the transmitted output power vs. frequency while the return loss is the reflected power vs. frequency. In the time domain, the insertion loss and return loss is equivalent to the TDT and TDR plots respectively. As you can see, the return loss matches pretty well; just like the TDR plot we observed earlier, but It is only obvious when we view the insertion loss plot as to the real reason for the eye discrepancy of Figure 3.

Notice the first resonant null at approximately 4.5 GHz. This null represents the quarter wave resonant frequency fo, and is due to the long 269 mil via stub. The other null at 13.5GHz is the 3rd harmonic of fo. The longer the stub length, the lower the resonant frequency. When there is a null at or near one-half the bit rate, then the eye will be devastated. In our example, 4.5GHz is approximately half of 10GB/s and as you can see from Figure 3 the resultant eye is totally closed.

But the S-parameters tell us even more. We can use them to confirm the rule of thumb used earlier with respect to the rise time of the signal being greater than, or equal to, 3 times the delay through the via discontinuity.

If you study the return loss plot, you will see there is an excellent match up to about 1.83GHz. This is the effective bandwidth for which the capacitor model is good for. Put another way, a bandwidth of 1.83GHz means you could use an equivalent capacitor model for the via for bit-rates up to 3.6GB/s.

Equation 1 is a commonly used to convert 3dB bandwidth to equivalent 10-90 rise time. Substituting 1.83 GHz for the 3dB bandwidth, the rise time equals approximately 185 ps.

Equation 1

When you divide 185 ps by 3, you end up with approximately 62ps compared to approximately 60ps for the propagation delay through the via we originally determined earlier.

Figure 5 is a summary of a simulation with the transmission line length reduced to 18 inches to reduce the rise time to 185 ps. As you can see the transmission line via model’s eye at 3.6 Gb/s is just starting to distort while the capacitor model is still relatively smooth; confirming our bandwidth rule of thumb. Using a capacitor as a via model past this bit-rate will result in optimistic results and long nights when your 10 Gig prototype hits the lab.

So now you see what I mean when I say that vias are capacitive, but not necessarily capacitors.

Figure 5 Eye comparison at 3.6Gb/s. Top topology uses 33 Ohm transmission lines for both the through and stub portion of the via. The bottom topology models the via with a 50 Ohm transmission line to represent the delay of the through portion and a 1.9pf capacitor to represent the excess capacitance. Modeled and simulated with Agilent ADS.

For more Information:

If you liked this design note and want to learn more, or get more details on modeling vias using transmission lines, you can visit my web site, LAMSIM Enterprises.com , and download a copy of the white paper I wrote along with Eric Bogatin and Yazi Cao titled, “Method of Modeling Differential Vias” .

While you are there, feel free to investigate my other white papers and publications.

If you would like more information on our signal integrity and backplane services, or how we can help you achieve your next high-speed design challenge, email us at: info@lamsimenterprises.com.

The Poor Man’s PCB Via Modeling Methodology

You are a backplane designer and have been assigned to engineer a new high-speed, multi-gigabit serial link architecture from several line cards to multiple fabric switch cards across a backplane. These links must operate at 6GB/s day one and be 10GB/s (IEEE 802.3KR) ready for product evolution. The schedule is tight, and you need to come up with a backplane architecture to allow the rest of the program to progress on schedule.

You come up with a concept you think will work, but the backplane is thick with over 30 layers. There are some long traces over 30 inches and some short traces of less than 2 inches between card slots. There is strong pressure to reuse the same connector you used in your last design, but your gut tells you its design may not be good enough for this higher speed application.

You come up with a concept you think will work, but the backplane is thick with over 30 layers. There are some long traces over 30 inches and some short traces of less than 2 inches between card slots. There is strong pressure to reuse the same connector you used in your last design, but your gut tells you its design may not be good enough for this higher speed application.

Finally, you are worried about the size and design of the differential via footprint used for the backplane connectors because you know they can be devastating to the quality of the received signal. You want to maximize the routing channel through the connector field, which requires you to shrink the anti-pad dimensions, so the tracks will be covered by the reference planes, but you can’t easily quantify the consequences on the via of doing so.

You have done all you can think of, based on experience, to make the vias as transparent as possible without simulating. Removal of non-functional pads on the inner layers, and planning to back-drill the connector via stubs will help, but is it enough? You know in the back of your mind the best way to answer these questions, and to help you sleep at night, is to put in the numbers.

So you decide to model and simulate the channel. But to do so, you need accurate models of the vias to plug into your favorite circuit simulator. But how do you get these? You have heard it all before; “for high-speed, the best way to model a via is with a 3D electro-magnetic field solver”. Although this might be true, what if you don’t have access to such a tool, because the cost is more than your company wants to spend, or because you don’t have the expertise nor the time to learn how to build a model you can trust to make a timely decision?

On top of that, 3D field solvers typically produce S-parameter behavioral models. Since they represent only one sample of a given construction, it is impossible to perform what-if, worst case, min/max analysis with a single behavioral model. Because of this, many iterations of the model are required; causing further delay in getting your answer.

A circuit model on the other hand, is a schematic representation of the actual device. For any physical structure, there can be more than one circuit model to describe it. All can give the same performance, up to some bandwidth. When run in a circuit simulator, it predicts a measurable performance of the structure. These models can be parameterized so that worst case analysis can be explored quickly.

The problem with a circuit model is that you often need a behavioral model to calibrate it, or need to use analytical equations to estimate the parameters. But, as my friend Eric Bogatin often says, “an OK answer NOW! is better than a great answer late”.

In the past, it was next to impossible to develop a circuit model of a differential via structure without a behavioral model to calibrate it. These behavioral models were developed through empirical formulas, measured data, or through the use of 3D EM field solvers.

Now, there is another way. I have nicknamed it, “The Poor Man’s PCB Via Modeling Methodology”. Here’s how it works.

Anatomy of a Differential Via Structure:

An example of a differential via structure, shown in Figure 1, is representative of vias used to connect surface mounted components or backplane connectors to internal layer traces.

An example of a differential via structure, shown in Figure 1, is representative of vias used to connect surface mounted components or backplane connectors to internal layer traces.

The via barrel is a plated through hole extending the entire length of a PCB stack-up. The outside diameter equals the drill diameter. The inside diameter is the finished hole size (FHS) after plating. Pads are used on layers to ensure there is sufficient copper for track attachment after drilling operation. When used in this fashion, they are referred to as functional pads. Anti-pads are the clearance holes in the plane layers allowing the via barrel to pass through them without shorting.

The via portion is the length of the barrel connecting one signal layer to another. It is often referred to as the through via since it is part of the signal net. The stub portion is the rest of the barrel extending to the outer layer of the PCB. In high-speed designs, a good rule of thumb to remember is that a via stub should be less than 300mils/BR in length; where BR is the bit rate in Gb/s.

Building a Simple Scalable Circuit Model:

On close examination of Figure 2, a differential via structure can be represented by a twin-rod transmission line geometry with excess capacitance (shown in red) distributed over its entire length. The smaller the anti-pad diameter, the greater the excess capacitance. This ultimately results in lower via impedance, causing higher reflections.

On close examination of Figure 2, a differential via structure can be represented by a twin-rod transmission line geometry with excess capacitance (shown in red) distributed over its entire length. The smaller the anti-pad diameter, the greater the excess capacitance. This ultimately results in lower via impedance, causing higher reflections.

In all high-speed serial link designs, it is common practice to remove all non-functional pads and to maximize the anti-pad clearance as much as practically possible. Oval anti-pads are often used in this regard to further mitigate excess via capacitance.

Figure 3 illustrates the equivalent circuit for a differential via that could be used in a channel topology simulation. Here it is modeled with Keysight ADS software using a coupled line transmission line model for each section. This equivalent circuit model can be scaled for any combination of layer transitions and integrated in any channel simulation scenario.

Since the cross-section of the via is constant throughout its length, the differential impedance of all sections of the via are the same. We only need to know the physical length of each segment and the effective dielectric constant (Dkeff) to get the time delay of each segment.

Since the cross-section of the via is constant throughout its length, the differential impedance of all sections of the via are the same. We only need to know the physical length of each segment and the effective dielectric constant (Dkeff) to get the time delay of each segment.

When driven differentially, the odd-mode parameters of each via are of major importance. Since the even-mode parameters have no impact on differential performance, both odd and even-mode parameters are set to the same values in the model.

The challenge then is to calculate the odd mode impedance (Zodd), representing the individual via impedance (Zvia), of a differential via structure and the effective dielectric constant (Dkeff) based on its geometry. Simple equations are used to determine these parameters.

Developing the Equations:

Anti-pads can vary in size and shape. They can be anything from round, to oval around each via, or even a large oval surrounding both vias as illustrated in Figure 4. Square, or rectangular variations (not shown) are similar.

Referring back to Figure 2, we see the structure of each via looks a lot like two coaxial transmission lines with the inner layer reference planes acting like a shield. Electrostatically this is a good approximation, but because the shield is not continuous, the magnetic fields are not contained like they are in a coaxial structure. Instead they behave more like magnetic fields around a twin-rod structure.

So here lies the secret in modeling a differential via. We take the best of both geometries to calculate the odd-mode impedance representing Zvia.

For inductance, we will use the odd-mode inductance formula from the twin-rod transmission line geometry to calculate Lvia :

Referring to Figure 4, we then calculate the odd-mode capacitance for Cvia derived from an approximate formula for an elliptic coaxial structure developed by M.A.R. Gunston in his book, “Microwave Transmission Line Impedance Data” . In the original formula, both shield (W’+b) and inner conductor (w+t) are elliptical in shape and are dimensioned as shown. When the anti-pads are circular, then ln[(W’+b) /(w+t)] reduces to just ln[b/t)]; which is the denominator in the Coax equation. If we use Gunston’s approximation to calculate Cvia, then the equation becomes:

Since conventional FR4 type laminates are fabricated with a weave of glass fiber yarns and resin, they are anisotropic in nature. Because of this, the dielectric constant value depends on the direction of the electric fields. In a multi-layer PCB, there are effectively two directions of electric fields.

The one we are most familiar with has the electric fields perpendicular to the surface of the PCB; as is the case of stripline shown here in Figure 5. The dielectric constant, designated as Dkz in this case, is normally the bulk value of the dielectric specified by the laminate manufacturer’s data sheet.

we are most familiar with has the electric fields perpendicular to the surface of the PCB; as is the case of stripline shown here in Figure 5. The dielectric constant, designated as Dkz in this case, is normally the bulk value of the dielectric specified by the laminate manufacturer’s data sheet.

The other case has the electric fields running parallel to the surface of the PCB, as is the case when a signal propagates through a differential via structure. In this situation, the dielectric constant, designated as Dkxy, can be15-20% higher than Dkz .

Therefore, assuming a nominal 18% anisotropic factor, Dkxy = 1.18(Dkz)

Now that we have defined Lvia, Cvia and Dkavg, Zvia can be estimated using the following equation:

But we are not finished yet. We still need to determine the effective dielectric constant (Dkeff) in order to accurately model the delay through the via and stub portion. Without the correct value, the quarter-wave resonant nulls in the insertion loss plot, due to the stub length, cannot be accurately predicted. The value for Dkeff is determined based on how much the via’s odd-mode impedance is decreased due to the distributed capacitive loading of the anti-pads.

To help us with this task, we start with the twin-rod formula. The odd-mode impedance (Zodd) is half the differential impedance (Ztwin), and is expressed as:

By substituting Equation 1 for Zodd into the equation above, and solving for Dkeff we eventually come up with the following equation:

Validating the Model:

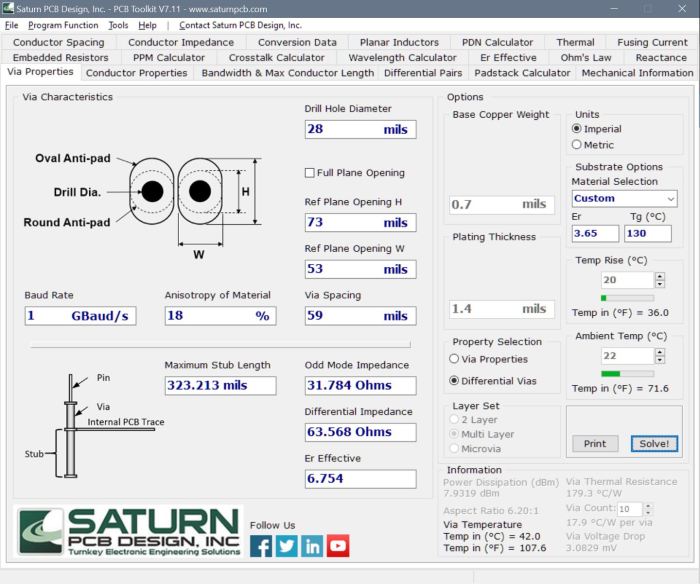

A simple 26 layer test vehicle was fabricated to compare the accuracy of the differential via circuit model to real vias. It consisted of two differential via pairs separated by 6 inches of 100 Ohm stripline differential pairs. Three sample via structures representing long, medium and short via stubs, as summarized in Figure 6, were measured using an Agilent N5230A VNA.

The differential vias had the following common parameters:

Via drill diameter; D = 28 mils

Via drill diameter; D = 28 mils

Center to center pitch; s = 59 mils

Oval anti-pads= 53 mils x 73 mils

Dk of the laminate = 3.65

Anisotropy in Dkxy = 18%

Zvia = Zstub = 31.7 Ohms (per Equation 1)

Dkeff = 6.8 (per Equation 2)

Agilent ADS software was used to model and facilitate simulation correlation of the measured data as captured in Figure 7. This simple model accounts for the discontinuity of the long through section and the long stub section. The top half is the measured channel using an S-parameter file. The bottom half is a circuit model of the channel. Since the probes were not calibrated out, they are part of the device under test. The balun transformers are used to facilitate the display of the S-parameter and TDR results.

The comparison between the measured and simulated results of the insertion loss and TDR response for the three via stub cases using this simple approximation methodology is summarized in Figure 8. The insertion loss plots, in the frequency domain, are shown on the left, while the TDR plots are shown on the right.

The resonant nulls in the SDD21 plots are due to the stub lengths. As you can see, the longer the stub, the lower the resonant frequency null. If this null happens at the Nyquist frequency of the bit rate, the eye will be totally closed. This is why we back-drill them out after the board has been fabricated.

The simulation correlation is excellent up to about 12 GHz. The TDR plots show excellent impedance matching and delay for all three cases, while the simulated stub resonant frequencies match the measured frequencies very well. As you can see, these simple approximations for Dkeff and Zvia are perfectly adequate in providing a quick and accurate circuit model for differential through hole vias typically used in backplane applications.

Summary:

As illustrated, a simple twin-rod model (Figure 2) is used as the basis for a practical differential via circuit modeling methodology. By using Equation 1 and Equation 2, you can quickly determine the odd-mode impedance and effective dielectric constant needed for the circuit model.

Of course, you should use this methodology first as a rough starting point to quickly estimate the performance of your differential via design. If your worst case topology simulations show the performance is marginal, then it is worth while to invest the time and money to develop a 3D full wave model to perform a more accurate analysis.

On the other hand, if you find this approximation shows the vias have little impact on the channel performance, it may be of greater value for you to invest your time and money in resolving other critical issues with your design.

Try it the next time you are losing sleep over your design challenges.

For more Information:

If you liked this design note and want to learn more, or get more details on this innovative via modeling methodology, you can visit my web site, LAMSIM Enterprises.com , and download a copy of the white paper I wrote along with Eric Bogatin and Yazi Cao titled, “Method of Modeling Differential Vias” .

While you are there, feel free to investigate my other white papers and publications.

If you would like more information on our signal integrity and backplane services, or how we can help you achieve your next high-speed design challenge, email us at: info@lamsimenterprises.com.

UPDATE: In collaboration with Saturn PCB, I am pleased to announce my differential via equations above have been incorporated in a new impedance calculator available now in Saturn PCB Tool Kit software suite.

Twin-rod and Rod-over-plane Transmission Line Geometries

In my last Design Note on coaxial transmission geometry, I mentioned it was one of three unique cross-sectional geometries that have exact equations for inductance and capacitance. The other two are twin-rod and rod-over-plane. All three relationships assume the dielectric material is homogeneous and completely fills the space when there are electric fields.

A common application for twin-rod geometry is twin-lead ribbon cable; once used for RF transmission between antenna and TV sets. With the popularity of cable and satellite TV over the years, twin-lead has given way to coaxial cable due to its superior noise rejection and shielding effectiveness.

If we look at Figure1, we can see the electromagnetic field relationship of a twin-rod geometry when it is driven differentially. As current propagates along one rod, an equal and opposite current flows in the opposite direction along the other.

The right half of Figure 1 shows the magnetic-field loops and direction of rotation around each rod. Only one loop is shown for clarity, but the number of loops is a function of the amount of current and the length of the rods. The counter-rotating loops of current forms a virtual return at exactly one half of the space between the two rods. We call this a virtual return because if we were to put a conducting plane in the same position, the electromagnetic fields would look exactly the same.

Figure 1 Twin-rod geometry showing electromagnetic field relationship.

In his book, “Signal Integrity Simplified”, Eric Bogatin defines the loop inductance as, “the total number of field line loops around a conductor per amp of current”, and the loop self-inductance as, “the total number of field line loops around a conductor per amp of current in the same loop” . Applying these definitions to the figure, the loop inductance (L) is the inductance between the two rods, and the loop self-inductance (L/2) is the loop self inductance to the virtual return plane; equal to one half the loop inductance.

Likewise, the left half of Figure 1 shows the electric field with a capacitance (C) between the two rods, and twice the capacitance (2C) from each rod to the virtual return plane.

The relationships between capacitance, inductance and impedance of a twin-rod geometry are described by the following equations:

Where:

Ctwin = Capacitance between twin-rods – F

Ltwin = Loop Inductance between twin-rods – H

Zdiff = Differential impedance of twin-rods – Ω

Dk = Dielectric constant of material

Len = Length of the rods – inches

r = Radius of the rods – inches

s = Space between the rods – inches

Because the electro-magnetic fields create a virtual return plane at exactly one half of the spacing between the rods, each rod behaves like a single rod-over-plane geometry as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Electromagnetic fields comparison of Twin-rod (left) vs. Rod-over-plane (right) geometries.

Whenever an AC current carrying conductor is in close proximity to a conducting plane, as is the case for rod-over-plane, some of the magnetic-field lines penetrate it. When the current changes direction, the associated magnetic-field lines also change direction; causing small voltages to be induced in the plane. These voltages create eddy currents, which in turn produce their own magnetic-fields.

Eddy current-induced magnetic-field line patterns look exactly like magnetic-field lines from an imaginary current below the plane; located the same distance as the real current above the plane. This imaginary current is called an image current, and has the same magnitude as the real current; except in the opposite direction [1]. The image current creates associated image magnetic-field lines in the opposite direction of the real field lines. As a result, the real magnetic-field lines are compressed between the rod and the plane. Since the rod-over-plane geometry has only one rod, the loop inductance is the same as the loop self-inductance.

For a twin-rod geometry, the odd mode capacitance is the capacitance of each rod to virtual return plane and is equal to twice the capacitance between rods.

Likewise, the odd mode inductance is the inductance of each rod to virtual return plane and equal to one half the inductance between rods.

The odd mode impedance of each rod is half of the differential impedance, and is equivalent to the rod-over-plane impedance.

[1] “Signal Integrity Simplified”, Eric Bogatin

Coaxial Transmission Line Geometry

The coaxial (coax) transmission line geometry, described by Figure 1, consists of a center conductor; imbedded within a dielectric material; surrounded by a continuous outer conductor; also known as the shield. All share the same geometric center axis; hence the name coaxial. It is common practice to transmit the signal on the center conductor, while the outer conductor provides the return path for current back to the source. The shield is usually grounded at both ends.

Figure 1 Example of a coaxial transmission line geometry and the electromagnetic

field patterns with respect to the current through the structure.

As the signal propagates along the transmission line, an electromagnetic field is set up between the outer surface of the center conductor and the inner surface of the shield. As illustrated in red, the electric E-field pattern sets the capacitance per unit length, and the magnetic H-field, in blue, sets the inductance. For the center conductor, the “X” represents current flowing into the page and the “.” (dots) within the shield ring is current flowing out of the page.

Figure 2 describes the magnetic-field relationship for a coax geometry. As current propagates along the center conductor, concentric magnetic-field lines (blue) are created in the direction as shown following the right hand rule.

Whenever an AC current carrying conductor is in close proximity to a conducting plane, some of the magnetic-field lines penetrate it. If this plane totally surrounds the inner conductor, it becomes the outer conductor in a coax geometry, and some of the magnetic-field lines penetrate the entire circumference. When the current changes direction, the associated magnetic-field lines also change direction, causing small voltages to be induced in the outer conductor. These voltages create eddy currents, which in turn, produce their own magnetic-fields.

Whenever an AC current carrying conductor is in close proximity to a conducting plane, some of the magnetic-field lines penetrate it. If this plane totally surrounds the inner conductor, it becomes the outer conductor in a coax geometry, and some of the magnetic-field lines penetrate the entire circumference. When the current changes direction, the associated magnetic-field lines also change direction, causing small voltages to be induced in the outer conductor. These voltages create eddy currents, which in turn, produce their own magnetic-fields.

Eddy current-induced magnetic-field line patterns look exactly like magnetic-field lines (grey) from imaginary currents surrounding the outer conductor. These imaginary currents are referred to as image currents, and have the same magnitude as the real current; except they are in the opposite direction [1]. For simplicity, there are only eight image currents shown. But in reality, there are many more; forming a continuous loop of imaginary currents on a radius equal to twice the radius of the outer conductor to the center of the circle. The image currents create associated image magnetic-field lines in the opposite direction of the real field lines. As a result, the real magnetic-field lines are compressed and are entirely contained within the outer conductor.

The outer conductor thus forms a shield preventing external magnetic-fields from coupling noise onto the main signal and likewise, prevents its own magnetic field from escaping and coupling to other cables or equipment. This is why it is a popular choice for RF applications.

The nice thing about a coaxial transmission line is you can use equations to calculate the exact inductance and capacitance per unit length. There are only two other geometries that can do the same. They are, twin-rod and rod-over-plane; which I will cover at a later time in separate design notes.

The relationships between capacitance, inductance and impedance can be expressed by the following equations:

Ccoax = Capacitance – F

Lcoax = Inductance – H

Zo = Characteristic Impedance – Ohms

Dk = Effective Dielectric constant

Len = Length of the rods – inches

D1 = Diameter of conductor

D2 = Diameter of shield

The coaxial structure can be flexible or semi-rigid in construction. Flexible coax is used for cable applications; like distributing cable TV or connecting radio transmitters/receivers with their antennas. To achieve its flexibility, the shield is usually braided and is protected by an outer plastic sheathing. Being flexible, the same cable can be reconfigured for different equipment applications.

Semi-rigid coax, in comparison, employs a solid tubular outer shield, which yields 100% RF shielding, and enables the dielectric material and center conductor to maintain a constant spacing; even through bends. If you have ever worked on your automobile brakes, semi-rigid coax resembles the rigid brake lines routed through the chassis to the wheels. Semi-rigid coax is usually used for microwave applications where optimum impedance control is required. A bending tool is needed to form it to a consistent radius. After initial forming and installation, it is not intended to be flexed or reconfigured.

[1] “Signal Integrity Simplified”, Eric Bogatin

PCB Vias – An Overview

Vias make electrical connections between layers on a printed circuit board. They can carry signals or power between layers. For backplane designs, the most common form of vias use plated through hole (PTH) technology. They connect the pins of connectors to inner signal layers. A PTH via is formed by drilling a hole through the layers to be connected and then copper plating it.

Vias make electrical connections between layers on a printed circuit board. They can carry signals or power between layers. For backplane designs, the most common form of vias use plated through hole (PTH) technology. They connect the pins of connectors to inner signal layers. A PTH via is formed by drilling a hole through the layers to be connected and then copper plating it.

High Density Interconnects (HDI) is another via technology used to form very small vias where drilling holes, using a conventional drill bit, is impractical. Also known as micro-vias, this technology creates the hole with a laser before plating.

Via Aspect Ratio

Via aspect ratio is defined as the ratio of the circuit board thickness to the smallest unplated drilled hole diameter. It is an important metric you need to be aware of when specifying the minimum via hole size for your design, and designing your stack-up. For example, an unplated via with a drill diameter of 0.020 inches and a board thickness of 0.200, would have an aspect ratio of 10:1. The smaller the aspect ratio, the more consistent the plating is throughout the length of the via. It is desirable to have 2 mil plating thickness for the via walls. Large aspect ratio vias tend to have more plating at each end compared to the middle. This increases the chance of cracked via barrels due to z-axis expansion while soldering.

An aspect ratio of 6:1 pretty much ensures your board can be fabricated anywhere. Most high-end board shops have the capability of fabricating boards with 10:1 aspect ratio; for drill diameters of less than 0.020 inches. Practically, the smallest drill diameter used for a through holed via is 0.013 inches. At 10:1, the maximum board thickness would be 0.130 inches.

For drill diameters larger than 0.020 inches, the max aspect ratio can be anywhere from 15:1 to over 20:1; depending on the board shop. Since backplane via hole size is driven by the compliant pins of the connector, it is best to work with your board shop to determine the maximum board thickness they can fabricate with the minimum finished hole size (FHS) specified in the design.

Via Configurations

The following lists the various via configurations you might expect to find on any multi-layer PCB design:

-

Stub Via

-

Through Via

- Blind or Micro-via

-

Buried Via

-

Back-drilled Via

Stub Via

The Stub Via is the most common via configuration found in PCBs today. As illustrated, there are two variations; Stub Via A and Stub Via B.

The Stub Via is the most common via configuration found in PCBs today. As illustrated, there are two variations; Stub Via A and Stub Via B.

For the Stub Via A example, it shows the through portion starting from the top layer and ending at some inner layer. The stub portion is the remaining portion continuing from the inner layer junction to the bottom layer.

The Stub Via B example shows the through portion originating from one internal signal layer and terminating on another internal signal layer. In this scenario, there are two stubs. The first stub is from the first internal layer junction to the top layer; the second stub is from the second internal layer junction to the bottom layer.

Through Via

Through vias are the oldest and simplest via configurations originally used in 2-4 layer PCB designs. Since the signals originate and terminate from the outer layers of the PCB, there are no stubs. In multi-layer PCB applications, they are an inexpensive way to eliminate the resonance effects caused by stubs where other mitigation techniques are not practical or are too expensive.

Through vias are the oldest and simplest via configurations originally used in 2-4 layer PCB designs. Since the signals originate and terminate from the outer layers of the PCB, there are no stubs. In multi-layer PCB applications, they are an inexpensive way to eliminate the resonance effects caused by stubs where other mitigation techniques are not practical or are too expensive.

Blind/Buried Via

Blind and buried vias are just like any other via, except they do not go all the way through the PCB. A Blind Via connects one or more internal layers to only one external layer. Controlled-depth drilling is used to form the holes prior to plating.

Blind and buried vias are just like any other via, except they do not go all the way through the PCB. A Blind Via connects one or more internal layers to only one external layer. Controlled-depth drilling is used to form the holes prior to plating.

A buried via, on the other hand, is a plated hole which is completely buried within the board. It connects one or more internal layers and does not connect to an external layer. Using buried via technology is costly because the inner layers being interconnected need to be fully fabricated and plated before final lamination of the entire PCB.

A micro-via is a form of blind via. Because the holes are so small (0.006 inches or less), they are formed using lasers, and cannot penetrate more than one or two layers at a time. They are most commonly used in high-density PCB designs like cell phones, or in FPGA and custom ASIC chip packaging.

Back-drilled Via

High speed point-point serial link based backplanes are often thick structures; due to the system architecture and card-card interconnect requirements. Back-drilling the via stub is common practice on thick PCBs to minimize stub length for bit-rates greater than 3Gb/s.

High speed point-point serial link based backplanes are often thick structures; due to the system architecture and card-card interconnect requirements. Back-drilling the via stub is common practice on thick PCBs to minimize stub length for bit-rates greater than 3Gb/s.

Back-drilling is a process to remove the stub portion of a PTH via. It is a post-fabrication drilling process where the back-drilled hole is of larger diameter than the original PTH. This technology is often used instead of blind-via technology to remove the stubs of connector vias in very thick high-speed backplane designs. State of the art board fabrication shops are able to back-drill to within 8 mils of the signal layer to keep, so there will always be a small stub portion attached to the via.

Back-drilling is not without limitations. Smaller vias and tighter pitch driven by large pin count BGA packages makes back-drilling impractical in these applications; due to drill bit size and tolerance issues. Fortunately, smaller via diameters limit the maximum PCB thickness due to aspect ratio; thereby limiting the length of the stub to the board thickness. Careful planning the high-speed layers within the stack-up is one way to control stub length.

We worry about stubs in high-speed designs because they cause unwanted resonant frequency nulls which appear in the insertion loss plot of the channel. If one of these frequency nulls happen to line up at or near the Nyquist frequency of the bit rate, the received eye will be devastated resulting in a high bit-error-rate; even link failure. A shorter stub length means these resonances will be pushed out further in frequency; ideally past the 5th harmonic of the Nyquist frequency as a rule of thumb.

We worry about stubs in high-speed designs because they cause unwanted resonant frequency nulls which appear in the insertion loss plot of the channel. If one of these frequency nulls happen to line up at or near the Nyquist frequency of the bit rate, the received eye will be devastated resulting in a high bit-error-rate; even link failure. A shorter stub length means these resonances will be pushed out further in frequency; ideally past the 5th harmonic of the Nyquist frequency as a rule of thumb.

Rules of thumb, in general, are no substitute for actual modeling and simulation. You should never depend on them to sign-off the final design; but you can use them to gain some intuition before hand. With that in mind, you can estimate the maximum stub length in inches using the following equation:

Where:

L Stub_max = maximum stub length in inches.

Dkeff = effective dielectric constant of the material surrounding the via hole structure.

BR = Bit rate in GB/s.

For example, the maximum stub length at 5GB/s should be less than 0.120 inches in FR4 material with a Dkeff of 4.0 to ensure the first resonant frequency null is greater than 5 times the Nyquist frequency of the bit rate. If the stub length is greater than this, it does not mean the design will not work at 5GB/s. Depending on just how much longer it is means there will be less than optimum eye opening at the receiver.

If you know the length of the stub, you can predict the fundamental resonant frequency, using the following equation:

Where:

Stub_len = stub length in inches.

fo = fundamental resonant frequency in GHz

So, using the same Dkeff of 4.0, and stub length of 0.120 inches, we calculated in the above example, the first resonant frequency null would occur at approximately 12.3 GHz. If we assume this is the 5th harmonic, then the Nyquist frequency is approximately 2.5GHz and the bit rate is 5Gb/s; which is where we started.

PCB Cross-sectional Geometries

PCB cross-sectional geometries describe the details of the dielectric substrates, traces and reference planes within a PCB stack-up. Their physical relationship with one another can then be used to predict the characteristic impedance of the respective traces. There are only three generic cross-sectional geometries with variations within each. They are:

-

Coplanar

-

Microstripline

-

Stripline

Coplanar:

Coplanar geometry, or sometimes called coplanar waveguide (CPW), is a signal conductor sandwiched between two coplanar reference conductors or planes. These reference planes are usually ground. The characteristic impedance is controlled by the signal trace width and the gap between it and reference planes. This is a common transmission line structure for RF and microwave designs using single-sided printed circuit board technology. As a rule of thumb, the width of the reference plane on each side of the signal trace should be at least five times the distance between the left and right plane.

Coplanar geometry, or sometimes called coplanar waveguide (CPW), is a signal conductor sandwiched between two coplanar reference conductors or planes. These reference planes are usually ground. The characteristic impedance is controlled by the signal trace width and the gap between it and reference planes. This is a common transmission line structure for RF and microwave designs using single-sided printed circuit board technology. As a rule of thumb, the width of the reference plane on each side of the signal trace should be at least five times the distance between the left and right plane.

Microstrip line:

The microstrip line is the most popular transmission line geometry used in two or four layer printed circuit boards. The characteristic impedance is controlled by the signal trace width, on one side of the substrate, and the thickness of the substrate to the reference plane below it. The embedded microstrip line has the signal trace covered with prepreg or other dielectric material.

Cross section views below showing Microstrip line (left) and embedded microstrip line (right).

Stripline:

Cross section views below shows an example of single stripline (left) and dual stripline (right) geometries. These are geometries are typically found in multi-layer PCBs of 6 layers or more. The characteristic impedance is controlled by the trace width, thickness and its proximity to the reference planes above and below.

Single stripline has one signal layer sandwiched between two reference planes. If the signal layer is exactly spaced between the two reference planes, the geometry is called a symmetrical stripline; as opposed to an asymmetrical stripline, where the signal trace is offset from the center of the cross-section.

Dual stripline geometries have two signal layers sandwiched between reference planes, and are mainly used to save layers; caveat is a trace on one layer is routed orthogonal to the trace on the other to mitigate crosstalk.

Differential Pair Geometry:

Differential signaling is when a signal and its complement are transmitted on two separate conductors. These conductors are called a differential pair. In a PCB, both traces are routed together with a constant space between them as edge-coupled or broadside-coupled.

Edge-coupled routes the traces side-by-side on the same layer as microstrip or stripline. The advantage is that any noise on the reference plane(s) is common to both traces and thus cancelled at the receiver. Most differential pairs are routed this way.

Edge-coupled routes the traces side-by-side on the same layer as microstrip or stripline. The advantage is that any noise on the reference plane(s) is common to both traces and thus cancelled at the receiver. Most differential pairs are routed this way.

Broadside-coupled routes one trace exactly over the other on 2 separate layers as dual stripline. Since each trace is more tightly coupled to its adjacent reference plane than the opposite reference plane, any noise on the planes will not be common to both traces and thus, will not be cancelled at the receiver. Because of this, and the fact that it usually results in a thicker PCB, this geometry is rarely used.

Odd-Mode Impedance:

Consider a pair of equal width microstrip line traces, labeled 1 and 2, with a constant spacing between them. Each individual trace, when driven in isolation, will have a characteristic impedance Zo, defined by the self-loop inductance and self-capacitance of the trace with respect to the reference plane.

Consider a pair of equal width microstrip line traces, labeled 1 and 2, with a constant spacing between them. Each individual trace, when driven in isolation, will have a characteristic impedance Zo, defined by the self-loop inductance and self-capacitance of the trace with respect to the reference plane.

When a pair of traces are driven differentially, the mode of propagation is odd. If the spacing between the transmission lines is close, there will be electromagnetic coupling between the two traces. This coupling is defined by the mutual inductance and capacitance.

The proximity of the traces to a reference plane(s) influences the amount of electromagnetic coupling between traces. The closer the traces are to the reference plane(s), the lower the self-loop inductance and stronger self-capacitance to the plane(s); resulting in a lower mutual inductance, and weaker mutual capacitance between traces. The result is a lower differential impedance.

A 2D field solver is usually used to extract the parameters for a given geometry. Once the RLGC parameters are extracted, an L C matrix can be set up as follows:

The self-loop inductance and self-capacitance for trace 1 and 2 are L11, C11, L22, C22 respectively. The off diagonal terms in each matrix, L12, L21, C12, C21, are the mutual inductance and mutual capacitance. We use the LC matrix to determine the odd-mode impedance.

The odd-mode impedance is the impedance of one trace, of a differential pair, when driven differentially. It can be calculated by the following equation:

Where:

Zodd = odd mode impedance

Lo = self-loop inductance = L11 = L22

Co = self-capacitance = C11 = C22

Lm = mutual inductance = L12 = L21

Cm = mutual capacitance = |C12 |=|C21|

Even Mode Impedance:

When current flows down both traces, of the same polarity, the mode of propagation is even and the coupling is positive. The even mode impedance can be calculated using the following equation:

Differential Impedance:

The differential impedance is twice the odd-mode impedance:

Average Impedance:

When current flows down two traces randomly, as if they were single-ended, the mode of propagation is a combination of odd and even. The average impedance of each trace is affected by its proximity to the adjacent trace(s); calculated by the following equation:

Coupling Coefficient:

The coupling coefficient, Kcc, is a number that conveys the amount of electromagnetic coupling between two traces. Knowing the odd and even mode impedance, Kcc can be calculated by the following equation:

Backward Crosstalk Coefficient:

Two traces near one another will couple a portion of its own signal to the other. If we consider one trace as the aggressor, and the other as the victim, the amount of coupled noise travelling backwards on the victim’s trace, opposite to the aggressor’s direction, is called Near-End crosstalk (NEXT) or backwards crosstalk. The amount of coupled noise, travelling in the same direction as the aggressor’s direction, is called Far-End crosstalk (FEXT).

In stripline, there is little to no FEXT, but backwards crosstalk will saturate to a fraction of the amplitude of the aggressor’s voltage for the length of time the traces are coupled. This fraction of the aggressor’s voltage is called the backward crosstalk coupling coefficient Kb. It is equal to one half of the coupling coefficient Kcc :

Example:

A 8-9-8 mil differential pair; with 12mil core; 12 mil prepreg; Dk=4; stripline geometry; 1/2 oz copper; has the following R L G C matrix extracted from a 2D field solver:

If the two traces are driven differentially, then the differential impedance is 100 Ohms and there is 13% coupling of the two traces. On the other hand, if the traces are driven single-ended then the characteristic impedance of each trace is 53 Ohms. With 9 mils of space between them, the backward crosstalk is 7%.

If you increase the spacing between traces until Zodd equals approximately Zeven, the coupling will reduce to near zero, and there will be little backward crosstalk. Depending on your design and your noise budget, you may be able to live with a certain amount of backwards crosstalk. The only way to know the spacing between traces to achieve the budget is to plug in the numbers.

Acknowledgment:

I would like to thank my old Nortel colleague, the late Dick Goulette, for sharing these equations many years ago. They have served me well over the years.

Via Stub Termination -Brought to You by “The Stubinator”

Thick backplanes with long via stubs will cause unwanted resonances in the channel insertion loss compared to vias with little or no stub length as shown by the red and green traces in the plot of Figure 1. If these resonances occur at or near the Nyquist frequency of the bit rate, there will be little or no eye-opening left at the receiver.

Figure 1 Topology circuit model of 2 differential vias with 30 inches of PCB etch. Insertion loss plot of Long via-no stub (green); short via-long stub (red); stub terminated (blue). Received eye diagrams after optimized FFE receive equalization at 10GB/s. Modeled and simulated using Agilent ADS.

In a typical backplane application, the signal entering the via structure from the top will travel along the through portion until it reaches the junction of the internal track and stub. At that point, the signal splits with some of the signal continuing along the trace, and the rest continuing along the stub. If the signal was Arnold Schwarzenegger, he would say, “I’ll be back!”. Having done this gig before, he knows that when he reaches the end of the stub it’s like hitting a brick wall; there’s no where to go but back up the stub. Like Arnold, when the signal reaches the end of the stub, it reflects back up the stub. When it arrives at the same junction, a portion combines with the original signal and the rest continues back toward the source. If the round trip delay is half a cycle, the two waves are completely 180 degrees out of phase and there is cancellation of the original signal. The frequency where maximum cancellation occurs is called the ¼ wave resonant frequency, fo. Resonance nulls due to stubs in an insertion loss plot, like the one shown in Figure 1, occurs at the fundamental frequency fo and at every odd harmonic.

If you know the length of the stub (in inches) and the effective dielectric constant Dkeff, the resonant frequency can be predicted with the following formula:

(1)

It is common practice to reduce stub lengths in high-speed backplane designs by back-drilling the stubs as close as possible to the active internal signal layer. This is a complex and costly process involving setting individual drill depths on a per board basis. Special design features must be designed into the artwork to set correct back-drill depth. Furthermore, it is difficult to verify ALL back-drilled holes were drilled correctly. I know of a case where a backplane came back and one via (that they knew of) had a significantly longer stub than was specified. The problem showed up by accident when they were characterizing the channel using a VNA and saw an unexpected resonant null in the SDD21 insertion loss plot. When all was said and done, it turned out there was a glitch in the fabricator’s software controlling the back-drilling process. There is no practical way to find these faults; short of doing VNA measurements on 100% of the back-drilled holes. With hundreds of them in a typical high-speed backplane, the cost would be prohibitive. Thus we have to trust the fabrication process of the vendor(s).

If only there was a way to terminate the stub and get rid of all this back-drilling. Well there just might be a solution. After returning from last year’s DesignCon2010, I was intrigued by a paper presented by Dr. Nicholas Biunno on a new matched terminated stub technology developed by Sanmina-SCI Corporation. They call this technology MTSviaTM and it allows the embedding of metal thin-film or polymer thick film resistors within a PCB stack-up during its fabrication. I like to call it “The Stubinator”. They developed this technology as an alternative to back-drilling. The beauty of this is you can terminate all the high-speed via stubs on just one resistive layer at the bottom of the PCB.

Of course, for this to work, we need to terminate the vias with a resistance equal to the differential via impedance to be most effective. But how do we determine the via differential impedance without going through a bunch of trial and error builds? In a DesignCon2009 paper titled, “Practical Analysis of Backplane Vias” I coauthored with Eric Bogatin from Bogatin Enterprises L.L.C., Sanjeev Gupta and Mike Resso from Agilent Technologies, we showed how you can model and simulate differential vias as simple twin-rod transmission line structures using simple transmission line circuit models as shown in Figure 1. You can download a copy of this award-winning paper from my web site at: Lamsimenterprises.com .

After determining fo (either by measurement of a real structure or through 3D modeling) and solving for Dkeff by rearranging equation (1), the differential via impedance calculated using the following equation:

(2)

Where:

s = the center to center spacing of the vias

D = Drill diameter.

Example:

The differential vias used in the model of Figure 1 has the following parameters:

s = 0.059 in.

D = 0.028 in.

stub_length = 0.269 in.

Dkeff = 6.14 by Equation (1) and fo=4.4GHz ;

Zdiff = 66 Ohms by Equation (2).

By adding a 66 Ohm resistor across the bottom of each via stub in the model, the blue trace in the plot shows the stub resonance has completely disappeared at the expense of an additional flat loss of about -10dB. The eye has opened up nicely.

This “Stubinator” technology looks like it could be a promising alternative to back-drilling. It resolves many of the issues and limitations highlighted above. Combined with silicon that can accommodate the additional signal loading, it may extend the life of traditional copper interconnections for next generation of Ethernet standards beyond 10GB/s.

Fiber Weave Effect Timing Skew

Fiber weave effect timing skew is becoming more of an issue as bit rates continue to soar upwards. For signaling rates of 5GB/s and beyond, it can actually ruin your day. For example, the figure on the left shows a 5GB/s received eye is totally closed due to 12.7 inches of fiber weave effect. It was modeled and simulated using Agilent ADS software.

Fiber weave effect timing skew is becoming more of an issue as bit rates continue to soar upwards. For signaling rates of 5GB/s and beyond, it can actually ruin your day. For example, the figure on the left shows a 5GB/s received eye is totally closed due to 12.7 inches of fiber weave effect. It was modeled and simulated using Agilent ADS software.

So what is fiber weave effect anyways and why should we be concerned about it? Well, it’s the term commonly used when we want to describe the situation where a fiberglass reinforced dielectric substrate causes timing skew between two or more transmission lines of the same length. Since the dielectric material used in the PCB fabrication process is made up of fiberglass yarns woven into cloth and impregnated with epoxy resin, it becomes non-homogeneous.

The speed at which a signal propagates along a transmission line depends on the surrounding material’s relative permittivity (er), or dielectric constant (Dk). The higher the Dk, the slower the signal propagates along the transmission line. When one trace happens to line up over a bundle of glass yarns for a portion of its length, as illustrated by the top trace in the figure on the left, the propagation delay is different compared to another trace of the same length which lines up over mostly resin. This is known as timing or phase skew and is due to the delta Dk surrounding the respective traces.

The speed at which a signal propagates along a transmission line depends on the surrounding material’s relative permittivity (er), or dielectric constant (Dk). The higher the Dk, the slower the signal propagates along the transmission line. When one trace happens to line up over a bundle of glass yarns for a portion of its length, as illustrated by the top trace in the figure on the left, the propagation delay is different compared to another trace of the same length which lines up over mostly resin. This is known as timing or phase skew and is due to the delta Dk surrounding the respective traces.

Fiber weave effect is a statistical problem. It is not uncommon for PCB designs to have long parallel lengths of track routing without any bends or jogs. This is particularly true in large passive backplane designs. Because the fiber weave pattern tends to run parallel to the x-y axis, any traces running the same way will eventually encounter a situation of worst case timing skew if you build enough boards. This was demonstrated by Intel after compiling more than 58,000 TDR and TDT measurements over two years. In 2007, Jeff Loyer et al presented a DesignCon paper “Fiber Weave Effect: Practical Impact Analysis and Mitigation Strategies” where they published the data and proposed techniques to mitigate the effect of fiber weave skew. They showed statistically it is possible to have a worst case timing skew of approximately 16ps per inch representing a delta Dk of approximately 0.8.

In high speed differential signalling this is an issue because any timing skew between the positive (D+) and negative (D-) data converts some of the differential signal into a common signal component. Ultimately this results in eye closure at the receiver and contributes to EMI radiation.

You can calculate the timing skew using the following equation:

Where:

tskew = total timing skew due to fiber weave effect length (sec)

Dkmax= dielectric constant of material predominated by fiberglass.

Dkmin= dielectric constant of material predominated by resin.

c = speed of light = 2.998E+8 m/s (1.18E+10 in/s)

A practical methodology you can use to estimate the minimum and maximum values of Dk is by studying the material properties available from PCB laminate suppliers. Consider two extreme styles of fiberglass cloths used in modern PCB laminate construction as illustrated by the figure on the left. The loose weave pattern of 106 has the highest resin content of all the most popular weaves, while the tight weave pattern of 7628 has the lowest. Therefore, you could use the specified values of Dk for cloth styles 106 and 7628 to get Dkmin and Dkmax respectively. Once you have these and apply a tolerance, you can estimate the tskew .

A practical methodology you can use to estimate the minimum and maximum values of Dk is by studying the material properties available from PCB laminate suppliers. Consider two extreme styles of fiberglass cloths used in modern PCB laminate construction as illustrated by the figure on the left. The loose weave pattern of 106 has the highest resin content of all the most popular weaves, while the tight weave pattern of 7628 has the lowest. Therefore, you could use the specified values of Dk for cloth styles 106 and 7628 to get Dkmin and Dkmax respectively. Once you have these and apply a tolerance, you can estimate the tskew .

Example:

Assume Fr4 material; one inch of fiber weave effect; Dk106= 3.34(+/-0.05) and Dk7628= 3.97(+/-0.05), then timing skew is calculated as follows:

Modern serial link interfaces use differential signalling on a pair of transmission lines of equal length for interconnect between two points. In a DesignCon 2007 paper, “Losses Induced by Asymmetry in Differential Transmission Lines” by Gustavo Blando et al, they showed how intra-pair timing skew between the positive (D+) and negative (D-) data caused an increase in the differential insertion loss profile due to timing induced resonances. These resonances appear as dips in the differential insertion loss profiles of the channel as shown in the following figure:

This figure presents the results from an ADS simulation I did recently of a PCIe Gen2 channel running at 5GT/s. The eye diagrams are at the receiver after approximately 30” of track length chip to chip. The channel model was parameterized to allow for adjusting the fiber weave effect length as required.

As you can see, when the length of the fiber weave effect induced skew increases from 0 to 12.7 inches, the fundamental frequency nulls in the differential insertion loss plots decrease. These nulls occur at the fundamental frequency (fo) and every odd harmonic.

Also, the eye shows some degradation at 5.6 inches of fiber weave effect and starts to distort significantly after 7.8 inches. At 12.7 inches, fo equals the Nyquist frequency of the data rate (in this case 2.5GHz) and the eye is totally closed.

You can predict the resonant frequency ahead of time and use it to gain some intuition before you simulate and validate the results. If you know the total intra-pair timing skew, fo is calculated using the following equation:

Where:

fo = resonant frequency

tskew = total intra-pair timing skew

Example:

Using tskew = 16 ps/in we calculated above and using 12.7 inches from the last simulation results in the figure above, the fundamental resonant frequency null is:

You can find more details of this phenomena plus a novel way to model and simulate it from a recent White Paper I published titled, “Practical Fiber Weave Effect Modeling”. It, along with other papers, is found on my website at LamsimEnterprises.com.

Characteristic Impedance and Propagation Delay of a Transmission Line

A transmission line is any two conductors with some length separated by a dielectric material. One conductor is the signal path and the other is its return path. As the leading edge of a signal propagates down a transmission line, the electric field strength between two oppositely charged conductors creates a voltage between them. Likewise, the current passing through them produces a corresponding magnetic field. A uniform transmission line terminated in its characteristic impedance will have a constant ratio of voltage to current at a given frequency at every point on the line.

To ensure good signal integrity, it is important to maintain a constant impedance at every point along the way. Any change in the characteristic impedance results in reflections which manifests itself into noise on the signal. In any printed circuit board design, it is almost impossible to maintain a constant impedance of the transmission path from transmitter to receiver. Things like vias, non-homogeneous dielectric, thickness variation and other component paracitics all contribute to impedance mismatch. In high-speed designs, uncontrolled impedance can significantly reduce voltage and timing margins to the point where the circuit may be marginal or worst inoperable. The best you can do is to try to minimize each impedance discontinuity when they occur.

Lossy Transmission Line Circuit Model:

The circuit model for a lossy transmission line assumes an infinite series of two-port components as illustrated. The series resistor represents the distributed resistance with the units as ohms (Ω) per unit length. The series inductor represents the distributed loop inductance with the units as henries (H) per unit length. Separating the two conductors is the dielectric material represented by conductance G in siemens (S) per unit length. Finally, the shunt capacitor represents the distributed capacitance between the two conductors with units of farads (F) per unit length.

The circuit model for a lossy transmission line assumes an infinite series of two-port components as illustrated. The series resistor represents the distributed resistance with the units as ohms (Ω) per unit length. The series inductor represents the distributed loop inductance with the units as henries (H) per unit length. Separating the two conductors is the dielectric material represented by conductance G in siemens (S) per unit length. Finally, the shunt capacitor represents the distributed capacitance between the two conductors with units of farads (F) per unit length.

A 2D field solver is the best tool to extract these parameters from a given transmission line geometry. It assumes, however, that the same geometry is maintained through its entire length. Many spice like simulators need these RLGC parameters for their lossy transmission line models.

Given the RLGC parameters, the characteristic impedance can be calculated by the following equation:

Where:

Zo is the intrinsic characteristic impedance of the transmission line.

Ro is the intrinsic series resistance per unit length of the transmission line.

Lo is the intrinsic loop inductance per unit length of the transmission line.

Go is the intrinsic conductance per unit length of the transmission line.

Co is the intrinsic capacitance per unit length of the transmission line.

Lossless Transmission Line:

For the lossless transmission line model, Ro and Go are assumed to be zero. As a result, the equation reduces to simply:

Propagation Delay:

Propagation delay, as it relates to transmission lines, is the length of time it takes for the signal to propagate through the conductor from on point to another. Given the inductance and capacitance per unit length, the propagation delay of the signal can be determined by the following equation:

Where:

tpd is the propagation delay in seconds/unit length.

Lo is the intrinsic loop inductance per unit length of the transmission line.

Co is the intrinsic capacitance per unit length of the transmission line.

Relative permittivity is also known as relative dielectric constant . The number is a measure of an insulator material’s ability to transmit an electric field compared to a vacuum, which is 1. For simplicity, it is usually referred to it as just the dielectric constant, Dk.

Electromagnetic signals propagate at the speed of light through free space. When these signals are surrounded by insulating material other than air or a vacuum, the propagation delay increases proportionally. You can determine the propagation delay with a known Dk by the following equation:

Where:

Dk is the dielectric constant of the material.

c is the speed of light in free space = 2.998E8 m/s or 1.180E10 in/s.