The Imperfect Via: Modeling Challenges Impacting Simulation Accuracy

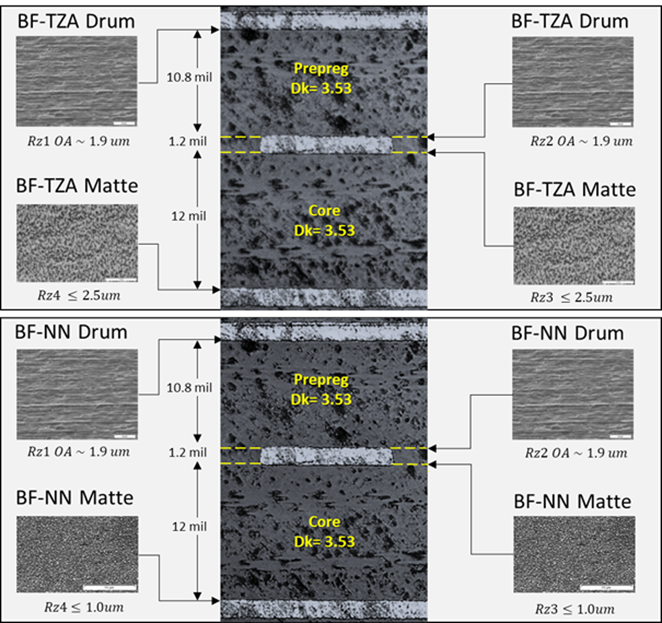

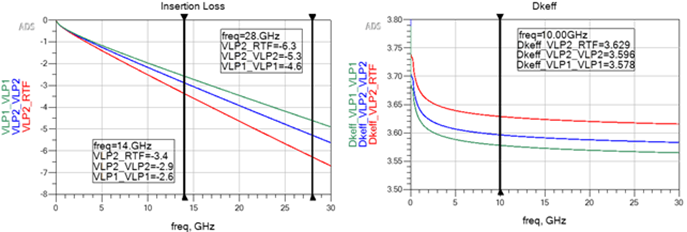

During DesignCon 2025, I had several side discussions about the findings presented in my DesignCon 2024 paper on dielectric anisotropy. A key concern raised was the discrepancy between measured results and simulations when converting the out-of-plane dielectric constant (Dkz) to in-plane Dkxy using my heuristic method. While Isola’s Tachyon 100G showed an average material anisotropy of approximately 4–6% across different glass styles, other researchers claimed that an anisotropy of 10–12% was necessary for accurate via simulation correlation.

What’s going on?

Glass-reinforced laminates dielectric properties vary depending on the orientation of the electric field within the structure. The in-plane dielectric constant (Dkxy) applies when the electric field is parallel to the fiberglass cloth, whereas the out-of-plane dielectric constant (Dkz) is when the field is perpendicular to it. Determining material anisotropy is strongly influenced by the specific test method used to extract dielectric properties and knowing the glass to resin volume ratios.

In my DesignCon 2024 paper, I defined percent anisotropy (Λ) using the following equation:

Equation 1

Efforts have been made to determine dielectric anisotropy using a quarter-wave resonant via structure. This approach relies on a via acting as a stub, which in theory, sounds like a sound method. Any quarter-wave resonant structure generates frequency nulls in the S21 insertion loss (IL) plots, as illustrated in Figure 1. The first resonant null at 13 GHz, corresponds to the fundamental frequency (f₀), with additional nulls appearing at each odd-harmonic.

Figure 1 S21 Insertion loss plot showing resonant nulls due to quarter-wave stub resonances.

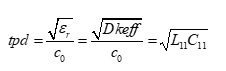

Given the speed of light (c₀), the length of the stub, and the effective dielectric constant (Dkeff) surrounding the via hole structure, the resonant frequency is predicted using:

Equation 2

Adjusting Dk values within a 3-D field solver to fit measured results based on as-fabricated PCB cross-section (x-section) dimensions provides an effective anisotropy (Λeff) specific to a similar via structure utilizing the same dielectric material. However, this does not represent the true anisotropy of the bulk dielectric.

While material anisotropy contributes to Dkeff surrounding a via hole structure, several other factors must also be considered.

One key factor is resin content. During the lamination process, the prepreg layers are pressed, leading to a decrease in resin volume. Since the glass volume remains unchanged, the overall Dk of the pressed laminate increases. This should be accounted for before applying my heuristic method to calculate Dkxy.

Another important consideration is drilled hole size. The actual dimensions of the via hole structure often differ from the specifications in the CAD database, which can impact simulation accuracy.

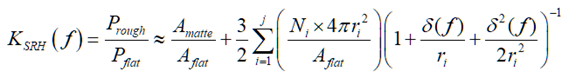

Lastly, via barrel roughness plays a significant role. Just as foil roughness influences Dkeff and time delay (TD) in transmission lines, via barrel roughness affects the surrounding dielectric properties. Increased via barrel roughness leads to higher TD and lowers the resonant frequency. Since quarter-wave stub resonance is used to determine Λeff, an increase in Dkeff and TD results in higher Λeff values.

To illustrate the impact of manufacturing tolerances on dielectric anisotropy, we can compare an ideal via structure with an actual fabricated version. An ideal via structure is depicted in Figure 2 (A). The via barrels are perfectly smooth and antipads align symmetrically across all layers. The dielectric surrounding the via is homogeneous. Many signal integrity (SI) engineers rely solely on the bulk Dk values provided in laminate suppliers’ Dk/Df construction tables without accounting for material anisotropy. Additionally, they often assume that the final pressed dielectric thickness matches the stackup design specifications and that the specified drill size aligns with the actual drill bit dimensions.

However, in reality, an as-fabricated x-section reveals deviations from ideal conditions, as shown in Figure 2 (B). Manufacturing tolerances result in misalignment of antipads across layers, and via barrels often exhibit rough surfaces with protruding whiskers which will affect dielectric properties. Moreover, since vias pass through a mixture of resin and fiberglass cloth, using bulk Dk values may not accurately represent material anisotropy. The true dielectric constant surrounding the via depends on the glass resin volume ratios of the pressed dielectric thickness and actual drill size used.

Figure 2 Cross-section illustration example of an ideal as designed via structure (fig A) and as fabricated (fig B).

Dielectric anisotropy plays a critical role in accurate PCB design and simulation. While quarter-wave resonant structures provide a useful method for extracting Λeff values, additional factors such as resin content, via barrel roughness, and manufacturing tolerances significantly influence the effective dielectric constant (Dkeff). By accounting for these real-world effects, simulation accuracy can be improved to better correlate with measured results.

To learn more, details can be found in this white paper.

PAM-2 vs. PAM-4: Simply Explained

Also Published in Signal Integrity Journal December 17, 2024

Figure 1 Comparison of NRZ (PAM-2) encoding versus PAM-4 encoding (A) and respective eye diagrams (B).

To keep up with the bandwidth demands of the industry, non-return-to-zero (NRZ) signaling has been replaced by pulse amplitude modulation level-4 (PAM-4) signaling. To maintain the same naming convention, NRZ signaling is now referred to as PAM-2. Both terms are acceptable.

PAM-2 has been widely used in various serial communication interfaces over the years due to its simplicity, robustness and lower cost to implement. The signal level remains constant during the bit interval, which helps in maintaining signal integrity with good margin. For decades it has been the workhorse for standards like PCIe and Ethernet 802.3, but as bit rates surpassed 32 Gb/s, PAM-4 signaling has become the standard.

PAM-4 signaling is used in high-speed data communication to effectively double the serial data rate without requiring an increase in channel bandwidth. It is commonly used in high-speed standards, such as 100G, 200G, and 400G Ethernet. It has also been adopted for PCIe Gen 6 and future Gen 7 standard. But unlike PAM-2, PAM-4 uses four distinct voltage levels to represent data.

As shown in Figure 1 (A), each bit time, or unit interval (UI) of a PAM-2 data channel, contains one symbol, which can represent either a logic zero or a logic one. In this case the bit rate is equal to the baud rate. In PAM-4 signaling, one symbol from each of the PAM-2 data channels are encoded into one bit stream using the Gray coding algorithm. The result is four voltage levels, with two symbols transmitted per UI, effectively doubling the bit rate for the same baud rate. For instance, if the bit rate is 56 Gb/s, the baud rate would be 28 GBaud (GBd).

The PAM-4 eye diagram in Figure 1 (B) shows three distinct eye openings, with on-third the voltage amplitude (VA), compared to the single eye opening in PAM-2. These levels are binary coded as 00, 01, 10, and 11. This difference in eye opening however, leads to a 9.6 dB reduction in signal to noise ratio (SNR). This means it’s more susceptible to noise, requiring more advanced signal processing and error correction. Fortunately, forward error correction (FEC) coding is used to compensate.

Through the course of my career, I have coined the phrase, “Never say never with copper. Silicon always finds a way!”. The shift from NRZ (PAM-2) to PAM-4 signaling has enabled higher data rates while maintaining bandwidth efficiency, despite its increased complexity and noise sensitivity. As our insatiable data needs continue to grow, due to artificial intelligence (AI) demands, the adoption of PAM-4 standard has paved the way for future PAM-level encoding schemes to address future bandwidth limitations, prolonging the life of copper interconnect.

PCB Laminate Anisotropy: The Impact on Advanced Via Modeling

Originally published in Signal Integrity Journal March 20, 2024.

As artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) challenge engineers to process more data faster, electronic design automation (EDA) tools are progressively integrating AI and ML to advance the design process. Many refer to this process as “shifting-left” or “shift-left.”

Several EDA tools often boast about their capability to extract and simulate nets from a PCB design file with a simple click of a button. However, if the user is not cognizant of dielectric anisotropy, or if the software does not account for it, the simulation results may be inaccurate. This could pose a challenge for simulating the next generation 112/224 Gbps interconnect due to the shrinking of already tight margins.

In the process of modeling a PCB via, it is crucial to obtain accurate dielectric material properties from reliable sources. A key factor in this regard is relative permittivity, or dielectric constant (Dk).

Copper clad laminate (CCL) panels used for PCB fabrication are a mixture of fiberglass and resin, cladded on one or both sides with copper. CCL suppliers use various test methods to determine Dk and dissipation factor (Df), which are eventually published in their construction tables. PCB fabricators and signal integrity (SI) and power integrity (PI) engineers then rely on these values, which are used to design PCB stackups and perform SI/PI analysis.

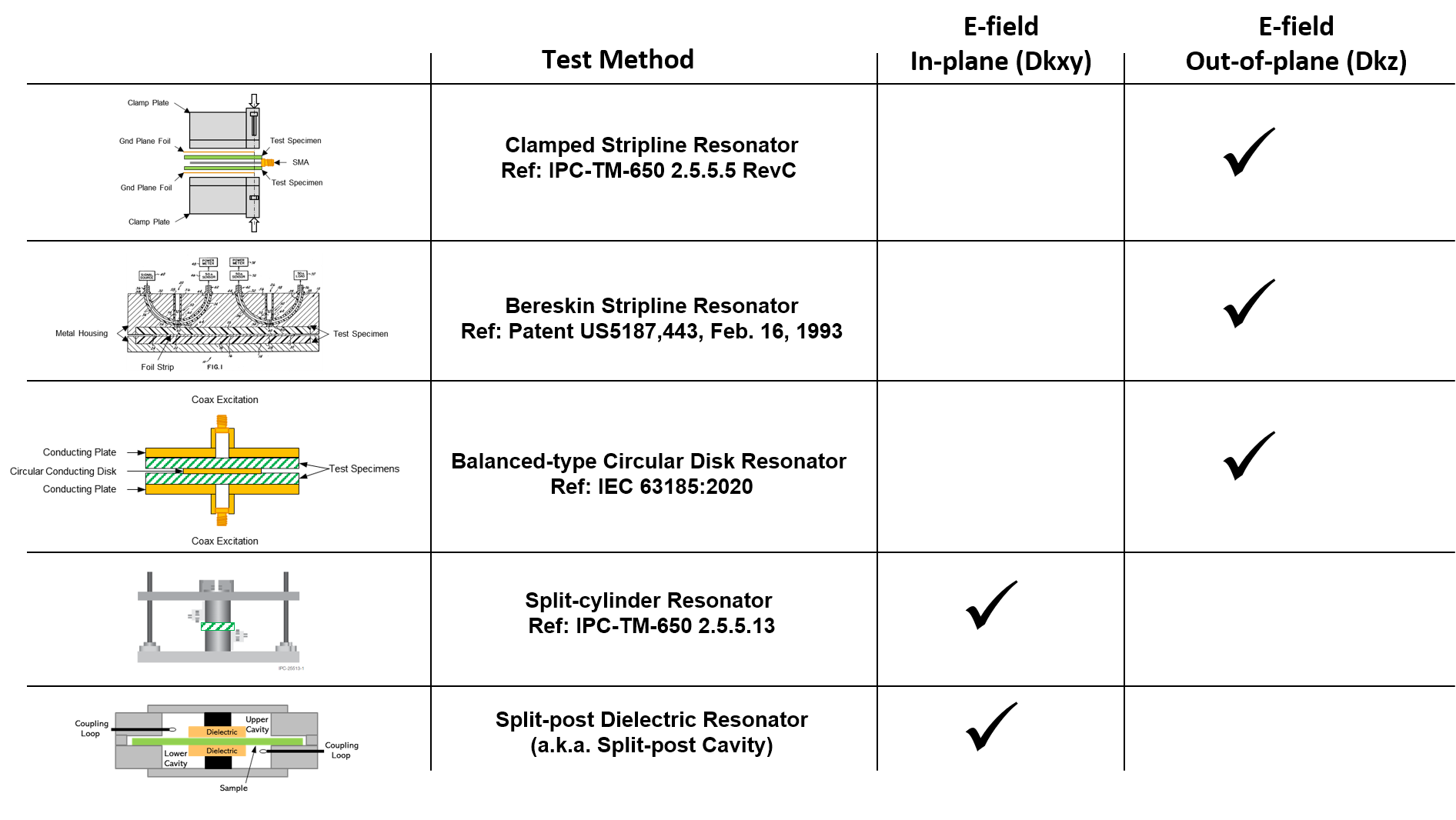

There are over a dozen test methods specified in Institute of Printed Circuits (IPC) specifications. These test methods were designed as a means of testing for quality control in a production environment and do not guarantee the numbers are accurate for design applications. Usually, CCL suppliers include a footnote disclaimer with similar wording to that effect in their construction tables.

PCB Laminate Anisotropy

All glass weave reinforced laminates are anisotropic, meaning dielectric properties will be different along different axes. Unfortunately, the publication of Dk by CCL suppliers does not include anisotropic properties required for precise impedance prediction and SI modeling.

The values of Dk can be different based on the specific test method used. Some methods give results from in-plane measurements, where the electric fields are parallel to the test sample. Conversely, other methods derive Dk from out-of-plane measurements, where the electric fields are perpendicular to the test sample.

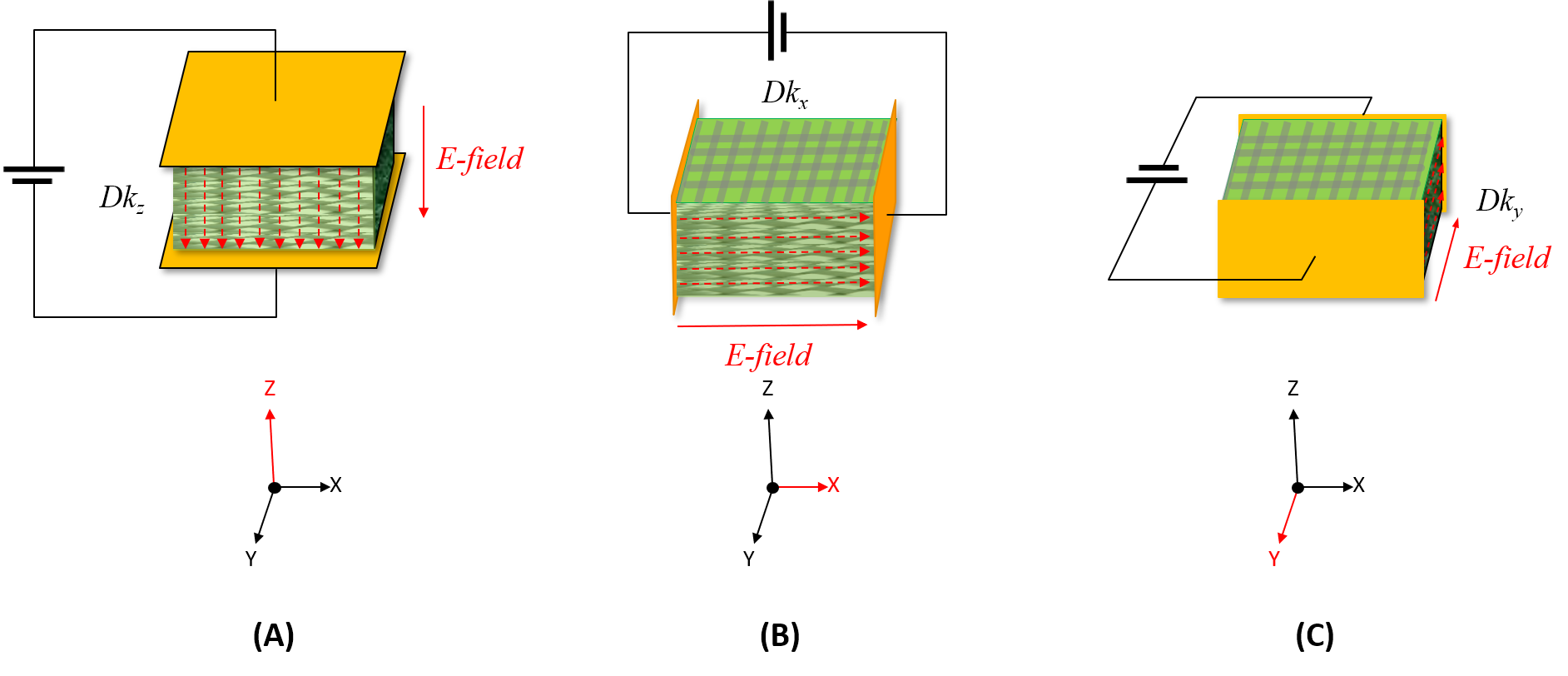

Figure 1a shows a block of fiberglass reinforced laminate, with the glass weave and copper plates running parallel to the x-y axis. When a DC potential is applied, a uniform electric field is out-of-plane in the z-direction, thereby creating a capacitor. Since the effective Dk is the ratio of actual structure’s capacitance, to the capacitance when the dielectric is replaced by air, we denote this ratio as Dkz.

Figure 1. E-field orientation relative to the glass weave reinforcement in PCB laminates when a DC electrical potential is applied: E-fields are out-of-plane with respect to the glass weave (A) and in-plane with the glass weave (B, C).

Figure 1b and 1c show that when the conducting plates are placed perpendicular to the direction of the glass weave, the E-fields align with the x or y axis and are in-plane. Even though there might be slight variations in the effective Dk in these directions, heuristically we assume they are equal and refer to them as Dkxy.

Depending on the test method used, Dk measured may be different due to the test fixture’s generated E-field orientation relative to the glass weave. Figure 2 summarizes E-field orientation when compared against popular test methods used by CCL suppliers. Dk obtained by these test methods are denoted as in-plane (Dkxy) or out-of-plane (Dkz).

Figure 2. Comparative table of E-field orientation and resulting Dkxy or Dkz across popular test methods employed by CCL suppliers.

Dkxy is typically higher compared to Dkz, depending on the glass resin mixtures of the sample tested as shown in Figure 3a.

Figure 3. Rule of solid mixtures: Parallel mixing rule is used when E-fields are polarized in Z-direction (A) and series mixing rule is used when E-fields are polarized in x-y direction (B).

The rules of solid mixtures1 can be used to estimate anisotropy of the glass and resin mixture. If the E-field is polarized in the z-direction, using a Dk of 6.8 for E-glass (Dkg), a Dk of 2.5 for resin (Dkr), volume fraction of resin (vresin = 0.7), and volume fraction of E-glass (vglass = 0.3), then the effective capacitance of each block is in series and Dkz is determined to be 3.09, using the parallel mixing rule defined by:

When the conductor plates are moved, as shown in Figure 3b, and the mixture is polarized such that the E-field is parallel to the x-y axis, then the effective capacitance is in parallel and Dkxy is determined to be 3.79, using the series mixing rule defined by:

Using Equation 3, Anisotropy (Λ) of the mixture reveals that Dkxy is 23% higher than Dkz.

Anisotropy Implications for Via Modeling

PCB transmission lines run parallel to the glass weave and E-fields are predominantly out-of-plane. Thus, Dkz is needed for accurate impedance modeling. Using Dkxy instead means the impedance predicted from the field solver will be lower than what would be measured if the board was made exactly as specified in the stackup.

In the case of modeling vias, it gets more complicated. In Figure 4, given a cross-section view of a typical via and stub, we observe the E-fields as the signal propagates, from left to right, along the microstrip transmission line on the top layer, through the via to an inner stripline layer 3 and continuing through the stub.

Figure 4. Cross-section view of E-fields as a 20 GHz signal propagates from the microstrip top layer through a via with stub to a stripline layer 3 (HFSS simulation courtesy of Juliano Mologni, Ansys4).

Using the same value for Dk when modeling transmission lines and vias leads to inaccurate results for one or the other. If the CCL supplier’s published numbers are out-of-plane, Dkz, then the impedance for transmission lines will be correct, while the via impedance will end up being lower than modeled. On the other hand, if the published numbers are in-plane, Dkxy, then the via impedance will be correct and the transmission line impedance will end up being higher.

Furthermore, using the wrong Dk for modeling via stubs will result in poor simulation correlation to measurements2 and potentially the loss of channel margin due to maximum stub length guidelines based on simulation analysis.3 This can be problematic for 112/224 Gbps interconnects by reducing already tight margins.

Figure 5 shows an example of this issue. A 26 mil (0.66 mm) pitch differential via with a 10 mil (0.254 mm) stub model was created in Keysight ADS5 via designer (see Figure 5a). A Dkz of 3.09 and Dkxy of 3.79 from Equation 1 and Equation 2 were used in the model for comparisons. After finite element method (FEM) simulation, S-parameters were saved in touchstone format and simulated in the circuit schematic shown in Figure 5b.

Figure 5. Simulated results for differential IL/RL (C) and TDR impedance (D) of a differential via model with 10 mil (0.254 mm) stub using Dkz of 3.09 (red plots) and Dkxy of 3.79 (blue plots) for laminate. Modeled and simulated with Keysight ADS5 via designer.

Figure 5c compares differential insertion loss (IL) and return loss (RL) and Figure 5d compares differential time domain reflectometer (TDR) impedance. The red plots are using out-of-plane Dkz and the blue plots are using in-plane Dkxy. As can be seen, when out-of-plane Dkz value is used in the model, it underestimates IL and impedance by approximately 8 Ohm. For 112 Gbps, the difference in loss at 28 GHz Nyquist frequency is ~ 0.3 dB. At 56 GHz Nyquist for 224 Gbps, the delta is ~ 0.9 dB, caused by the difference in stub resonant nulls at 106 and 95 GHz.

But this doesn’t tell the whole story. While it is widely known that short, highly reflective channels can negatively impact channel performance, the issue has been exacerbated by the introduction of 4-level pulse amplitude modulated (PAM4) signaling, which reduces the signal-noise ratio by 9.5 dB. As bit rates continue to increase exponentially, traditional IL/RL masks and eye diagrams are no longer sufficient for assessing channel quality.

Channel operating margin (COM)7 is a system-level metric approach adopted by the IEEE 802.3ck standard to validate the performance of a serial link. As part of COM, there is an effective return loss (ERL) metric that factors in reflections caused by impedance mismatches at the pins of the transmitter, receiver, and any other discontinuities between them. Thus, COM can be used to assess the impact of Dk anisotropy on key metrics.

A short channel representing a typical chip-to-chip (C2C) topology was modeled by concatenating touchstone files for vias and transmission lines using Keysight ADS5, as depicted in Figure 6b. The 2 in. (5.08 cm), 100 Ohm differential transmission line was modeled with Polar SI90006 using an out-of-plane Dkz value of 3.09.

Figure 6. Simulated TDR and COM results when Dkz was used for vias and transmission lines compared to when Dkxy was used for via models and Dkz used for transmission lines. When Dkz was used for all models COM and ERL passed (d), but when Dkxy was used for the via models, COM passes with reduced margins and ERL failed (E).

Figure 6a shows the differential TDR response obtained using a Dkz value of 3.09 for the via and transmission line models. As shown in Figure 6d, both COM and ERL passed when a short package model was used. When the via files were replaced with files modeled with Dkxy of 3.79, the differential TDR response is degraded, as shown in Figure 6c. Figure 6e shows that although COM passed, it had reduced margins and ERL failed.

Of course, this was an extreme example with high Dk anisotropy. Choosing a dielectric with low Dk glass and higher resin content would improve the results. But if you have a tight loss budget to begin with, using the wrong numbers could cause failure to meet compliance once your board is built and tested.

Summary

Since woven glass PCB substrates are anisotropic, EDA design and modeling software hoping to advance AI and ML algorithms should have provisions to model anisotropic material, especially via transitions.

It is important to have awareness of the test method used by CCL suppliers for accurate modeling and simulation. Using out-of-plane Dkz values instead of in-plane Dkxy values for via modeling can cause misleading simulation results, which may result in reduced margins and potential compliance test failures when the design is built and tested.

It is recommended that CCL suppliers provide anisotropic properties in their Dk/Df construction tables. In lieu of that, my DesignCon 2024 paper and presentation titled “A Heuristic Approach to Assess Anisotropic Properties of Glass-reinforced PCB Substrates” will be delving deeper into anisotropy to reveal how to calculate anisotropy from CCL suppliers’ Dk/Df construction tables. The full paper will be made available following the event.

April 3, 2024 update: The DesignCon paper is now available on my web site:

REFERENCES

-

P. S. Neelakanta, “Handbook of Electromagnetic Materials: Monolithic and Composite Versions and Their Applications,” CRC Press LLC, 1995.

-

L. Simonovich, E. Bogatin, and Y. Cao, “Differential Via Modeling Methodology,” IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 722–730, May 2011, doi: 10.1109/TCPMT.2010.2103313.

-

B. Simonovich, “Via Stubs – Are They all Bad?”, Signal Integrity Journal, March 10, 2017

-

ANSYS, Inc. Headquarters, Southpointe, 2600 Ansys Drive, Canonsburg, Pa., 15317, U.S.

-

Keysight PathWave Advanced Design System (ADS) [computer software], (Version 2023, Update 2).

-

Polar Instruments Si9000 [computer software], (Version 22.09.01).

-

IEEE802.3ck COM v3.70, computer software.

How Fiber Weave Effect Skew Can Affect Your High-speed Design

Fiber weave effect (FWE) skew, also known as glass-weave skew (GWS), is becoming more of an issue as bit rates continue to soar upwards. Today’s 56GB/s is state of the art in high-speed routers and 112 GB/s is just around the corner. While next generation PCIe, used in the personal computer and server industry, is rapidly moving to 64 GT/s.

Skew can come from any intra-pair asymmetries, such as: packages; ball-grid array (BGA) breakouts; intra-pair routing length mismatches; connectors and asymmetrical return path vias, to name a few examples. Many of these can be controlled by specifying tight constraints in the design. But, since FWE is statistical in nature, it can be most difficult to control the timing skew it causes, and at these data rates, it can actually ruin your day.

Figure 1 Fiber weave effect example of differential pair routing showing top trace routed over a low resin fill fiberglass bundle for a portion of its length while the bottom trace is routed over mostly higher resin fill. Timing skew between a positive (D+) and negative (D-) signals will cause a resonant null in the SDD21 insertion loss and convert some of the differential signal into a common signal component.

FWE is the term commonly used when a fiberglass reinforced dielectric substrate causes intra-pair timing skew of the same length. Since the dielectric material used in the printed circuit board (PCB) fabrication process is made up of glass yarns woven into cloth and impregnated with epoxy resin, it becomes non-homogenous.

As illustrated in Figure 1, when the top trace is routed over an area of low resin fill glass weave for a portion of its length, it will have a different propagation delay compared to the bottom trace routed over an area of high resin fill glass weave. The difference in delay is known as timing or phase skew.

The speed at which a signal propagates along a transmission line depends on the material’s relative permittivity (er), also known as dielectric constant (Dk). The higher the Dk, the slower the signal propagation.

Since modern serial link interfaces use differential signalling on a pair of transmission lines of equal length, any timing skew between a positive (D+) and negative (D-) signals will convert some of the differential signal into a common signal component. Ultimately this results in eye closure at the receiver and contributes to electro-magnetic interference (EMI) radiation.

Timing skew in the time domain manifests itself into a resonant null in the frequency domain, as shown in Figure 1. In this example, if the timing skew is equal to one-half unit interval (UI) of the baud rate, D+ and D- signals will be shifted 90 degrees and the resonant null will occur at the frequency of the baud rate.

You can predict the resonant frequency (fo) if you know the intra-pair timing skew (tskew) and FEW lengths using the following equation:

Equation 1

where:

lengthFWE = maximum FEW length

c = speed of light = 2.998E+8 m/s (1.18E+10 in/s)

Dkmin , Dkmax are the minimum and maximum effective Dk due to the glass weave.

When TDskew is equal to 1 UI, D+ and D- signals will be shifted 180 degrees and become in phase with one another. The resonant null will occur at the Nyquist frequency, equal to one-half of the baud rate, and the eye will be totally closed.

By definition, the baud rate is the number of symbols transmitted per UI. For non-return to zero (NRZ), the baud rate equals the symbol or bit-rate. For pulse amplitude modulated 4-level (PAM-4) signalling, there are two symbols per UI and the baud rate is one-half the bit rate. So, for 56 GB/s PAM-4, the baud rate is 28 GBd. For IEEE802.3bs, Ethernet 400G standard, the baud rate is 26.56 GBd, PAM-4 and is used for this study.

The skew issue is exacerbated for PAM-4 signalling, as shown in Figure 2. In these examples a simulated lossless transmission line was used to only show the effect of eye closure due to skew. Of course there is no such thing as a lossless transmission line, but it is a useful method to isolate the loss strictly due to skew. As shown in Figure 2 (a), with 0UI of skew, the channel loss is flat and eyes are wide open.

A resonant null in the frequency domain, due to FWE skew, behaves like a notch filter. Depending on the Q-factor, frequencies near resonance will be attenuated. If the resonant null occurs near the Nyquist frequency the eye will be reduced. In the example of Figure 2 (b), with 0.5UI, or 18.8 ps of skew, there is a resonant null at the baud rate and the insertion loss is -3 dB at 13.28 GHz Nyquist frequency. This causes an eye height (EH) reduction of 153 mV and an increase of 10 ps of jitter.

When skew is 1UI, or 37.65 ps, as shown in Figure 2 (c), the resonant null is at the Nyquist frequency and the eyes are totally closed. With a lossy channel and other impairments, eye closure will only get worse.

Figure 2 The effect of FEW skew on lossless transmission line example.

Total Skew Budget

As a rule of thumb, we usually strive to have an interconnect bandwidth (BW) to be five times the Nyquist frequency of the bit-rate. This follows many oscilloscope manufacturers’ specifications for risetime (RT) bandwidth product equal to 0.35.

Equation 2

RT x BW = 0.35

Five times Nyquist represents the 5th harmonic sinusoidal component of a Fourier series, shown in Figure 3. An interconnect BW up to the 5th harmonic preserves the integrity of the risetime down to 7% of the period (T) of the fundamental frequency (f1).

Equation 3

Thus, for a 26.56 GBd data signal, with a Nyquist frequency of 13.28 GHz, a BW of 66.4 GHz is needed to maintain a RT of 5.27 ps.

Figure 3 Fourier series to the 5th odd harmonics of the fundamental frequency

Some industry standards limit the total skew budget in a channel to 0.2UI from all sources. But is that enough for today’s PAM-4 systems?

Twenty percent of a UI will result in a resonant null at a frequency (f0) equal to 5 times the Nyquist frequency (fNq).

if;

Equation 4

then;

Equation 5

At 26.56 GBd that’s only 7.53ps!

But 0.2UI would obliterate the 5th harmonic of the Nyquist frequency. Historically, for non-return to zero (NRZ) and lower baud rates, there was more margin, but for PAM-4, with a -9.5dB signal to noise (S/N) penalty, 0.2UI may further strain channel margin.

For that reason, a good rule of thumb to follow, is making sure the first null occurs at the 7th harmonic of the Nyquist frequency; to maintain the integrity of the 5th harmonic frequency component. This means a total skew budget of 0.14UI:

Equation 6

Figure 4 compares 0.2UI and 0.14UI total skew budget vs common industry standard baud rates. As shown, there is an exponential decline in skew budget as baud rate increases. For 0.14UI, the total skew budget at 26.56 GBd is 5.27ps and at 56 GBd, it is only 2.5ps. Since this is the total skew budget, it doesn’t leave much left for the FWE skew budget!

Figure 4 Graph comparing 0.2UI (red) and 0.14UI (blue) total skew budget vs industry standard Gbaud rates.

Figure 5 compares two lossless differential pair simulations with, 0.14UI (a) and 0.20UI (b) of skew added. The eye diagrams show that with 0.22dB delta in insertion loss at 13.28GHz Nyquist, there is an additional 12 mV of reduction in center EH and an increase of 0.57ps of jitter; due to resonant null shift in frequency, down to 66.4 GHz (b).

Figure 5 Lossless differential pair simulation with 0.14UI (a) and 0.20UI (b) of skew added. With 0.22dB delta in insertion loss at 13.28GHz Nyquist, there is additional 12 mV loss in center EH and increase of 0.57ps of jitter due to resonant null shift in frequency down to 66.4 GHz (b).

The Reality

For a lossless channel, 12 mV seems insignificant. But that’s not reality. Real channels have loss and other impairments that will further erode the eye opening. Furthermore, many specifications have limits on the total loss.

The IEEE 802.3bs chip-module (C2M) spec [3] has a tight insertion loss (IL) mask spec of 10.2 dB at 13.28 GHz. Table 120E-1 of the same document specifies a minimum differential eye height (EH) of 32 mV and eye symmetry mask width (EW) of 0.22UI or 8.23ps at TP1a.

Figure 6 shows simulated results of IL and PAM-4 eye diagrams of a realistic chip C2M channel. Worst case power-voltage-temperature (PVT) was used for the transmitter model including the package. Figure 6 (a) shows the results of the inherent channel, with all impairments included. It has 1.7ps, or 0.045UI of skew as a baseline. The channel loss just meets the IL mask and the eyes meet the IEEE 802.3bs EH and EW with margin.

Figure 6 (b) and (c) increases total skew to the equivalent of 0.14UI, and 0.2UI respectively. As skew increases, the IL degrades due to decreasing resonant null frequency. At 0.14 UI (b), the IL is just starting to violate the IL mask near the Nyquist frequency break-point and the EH and EW are still within spec. But at 0.2UI (c), IL is slightly worse and the EH just fails the 32mV spec; but passes the EW spec.

The minimum eye heights and widths measured at 10-5 bit-error-ratio (BER) were:

a) 0.045UI (37; 37; 37) mV and (9.601; 9.789; 9.601) ps – EH/EW –PASS

b) 0.14UI (35; 34; 34) mV and (9.224; 9.601; 9.224) ps – EH/EW –PASS

c) 0.20UI (31; 30; 30) mV and (9.036; 9.036; 9.036) ps – EH –FAIL / EW –PASS

Figure 6 Simulated results of IL and PAM-4 eye diagrams of a realistic chip C2M channel when total skew is increased to 0.14 UI (b) and 0.20 UI (c) from the baseline 0.045 UI skew.

FWE Skew Budget

Since FWE is a function of glass weave style, resin chemistries, trace geometries and stackup parameters, to name a few things, it is difficult to establish an exact delta Dk from data sheets. A practical study from [1] showed a maximum FWE skew of 45 ps, over 7.5 inches. This represents 6 ps/inch of FWE skew. The boards were designed as stripline construction, using double layer 1035 spread-weave glass for the Megtron-6 cores and prepregs.

This is a realistic study for modern multi-gigabit designs. But the complexity of multi-ply layups does not ensure the glass bundles of each ply would perfectly align above and below the traces. In fact, when observing the cross-sections showed glass bundles of each ply were off-set from each other which would improve FWE skew results. Following the methodology from [2] would give a more pessimistic 9.46 ps/in, which you might experience in micro-strip with single layer construction.

If we budget 1 ps of skew for all impairments, like length matching, connectors, breakouts etc., we can establish a FWE skew budget for various baud rates. Figure 7 plots FWE UI skew budget vs baud rates assuming a total skew budget of 0.14 UI. We observe up to 10GBd or so, the 1ps of skew from other impairments is negligible. But after 10 GBd, it starts to impact FWE skew budget. At 26.56 GBd and 32 GBd it is approximately 0.11 UI and at 56 GBd it is only about 0.08 UI!

Figure 7 FWE UI skew budget vs baud rates assuming a total skew budget of 0.14 UI

With 6 ps/inch of FWE skew [1], the FWE lengths are calculated to meet 0.14UI total skew budget and plotted vs Gbaud rate, shown in red of Figure 8. If 9.46 ps/in is used, following the methodology from [2], the FWE lengths are shown in blue.

As we can see, there is an exponential decline in FWE length for an exponential rise in Gbaud rate. Above 10 GBd, FWE gets increasingly more difficult to control without further mitigation techniques. At 26.56 GBd and 6 ps/in of skew, the maximum length is 0.7 inches; at 56 GBd, it’s only 0.25 inches. But for 9.46 ps/in of skew, the lengths reduce to about 0.5 inch at 26.56 GBd and 0.2 inches at 56 GBd!

Popular FWE skew mitigation techniques include:

· Choosing a glass style where the glass strands are mechanically spread to fill in the resin rich windows.

· Zig-zag or random routing of differential pairs.

· Choosing a differential pair pitch to line up with glass style pitch. However, this is not always practical because the warp and fill yarns in different glass styles may have different pitches.

· Rotate artwork 7-10 degrees on the PCB panel.

Sometimes more than one of these techniques are needed.

Figure 8 FWE length budget vs GBaud rate assuming a total skew budget of 0.14 UI and tskew of 6 ps/in (red) and 9.46 ps/in (blue).

Summary and Conclusions

With bit rates above 25 GB/s, 0.2 UI total skew budget has shown to be insufficient for PAM-4 signalling for some industry standards. In order to mitigate the effect of skew on eye height and width, it is proposed 0.14 UI be used for total skew budget to maintain a channel bandwidth to at least seven times the Nyquist frequency of the baud rate.

Up to 10GBd or so, limiting the non-FWE skew to 1 ps from other impairments, has a negligible effect on 0.14 UI total skew budget. But after 10 GBd, it starts to reduce the FWE skew budget. At 26.56 GBd and 32 GBd it is approximately 0.1 UI and at 56 GBd it is only about 0.08 UI!

With larger and larger switch application specific integrated circuit (ASIC) packages and with tighter and tighter ball grid array (BGA) pitch packages, means reduced impedance-controlled line widths and space to break out of the BGA pin field. Similarly for routing through tight pitch backplane connectors. It is not uncommon to see BGA escape lengths to be on the order of 0.25 inches or more. And in most cases those breakouts are parallel to X-Y axis of the panel. At 56 GBd, that’s the entire skew budget! This then becomes unmanageable without further FWE skew mitigation techniques.

Of course, this analysis is based on worst case, and doesn’t mean if you violate this skew budget your system is broken. But what it doses show, is more detailed modeling and simulation of the channel is required with perhaps more consideration to include FWE skew budget in the channel model. This will present severe challenges on designing the next generation 112 Gb/s systems and choosing PCB dielectric material.

References

[1] B. Gore, S. McMorrow, “Vehicle for Insitu Glass Fabric Characterization”, EDICON 2017, Boston, USA

[2] L. Simonovich, “Practical Fiber Weave Effect Modeling”, White Paper, Issue 03, Lamsim Enterprises Inc., 3/2/2011.

[3] IEEE Std 802.3bs™-2017, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., 3 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10016-5997, USA

[4] Keysight Pathwave Advanced Design System (ADS) [computer software], (Version 2021 update2). URL: http://www.keysight.com/en/pc-1297113/advanced-design-system-ads?cc=US&lc=eng

Book Review: BOGATIN’S PRACTICAL GUIDE to TRANSMISSION LINE DESIGN and CHARACTERIZATION for SIGNAL INTEGRITY APPLICATIONS

Originally published Signal Integrity Journal March 20, 2023

I often get asked by young engineers what it takes to become a good SI/PI or EMC engineer. I quickly respond with, “What’s on your bookshelf?”, because I’m a firm believer you can never learn too much on a particular subject. So answering the same question about myself, I would say, “A lot of books by Dr. Eric Bogatin”.

I often get asked by young engineers what it takes to become a good SI/PI or EMC engineer. I quickly respond with, “What’s on your bookshelf?”, because I’m a firm believer you can never learn too much on a particular subject. So answering the same question about myself, I would say, “A lot of books by Dr. Eric Bogatin”.

You might ask, “Why so many of his books?”. The reason is Eric always has something new to teach me. Especially with one of his latest books, “BOGATIN’S PRACTICAL GUIDE to TRANSMISSION LINE DESIGN and CHARACTERIZATION for SIGNAL INTEGRITY APPLICATIONS”. The 603 page book is available in two formats, e-book and hard cover print. Both versions are available through Artech House.

I started with the e-book version, but later got the hard cover book because I’m old school and like to have hard copy books on my book shelf as a quick reference. If you are trying to decide which version to buy, I recommend the e-book. You see, Eric has trailblazed the industry, once again, with this version. If you have been following Eric’s teachings through his webinars and videos, you would now have the best of both worlds on your hard drive.

In the first chapter, Eric asks the question, “Do we really need another transmission line book?”, then goes onto explain his reason why we do. I would however, ask another question, “Do we really need a Different transmission line book?”.

Here’s why:

The e-book is multimedia. Eric has cleverly integrated video tutorials to reinforce the written text to further cement his teachings. By clicking on embedded hyperlinks to a secure web sight, you get to watch a short video related topic. It is like having Eric as your own personal virtual tutor you can watch over and over to strengthen the concepts he has described in the text.

The internet is full of content dealing with transmission lines. Much of the content you read is full of complex math equations and confusing explanations that is often been copied and filtered from other blog sights and articles for marketing click-bait. Some of it is just plain wrong or misinterpreted by the author. This just leads to more fear, uncertainty and doubt; a.k.a. FUD.

Instead, Eric Bogatin’s book starts with basic fundamentals of transmission lines explained and filled with practical examples and videos. At the end of each chapter there are review questions and the answers are found in the Appendix. By the end of the book, you will come away with the understanding of;

-

lossless vs lossy transmission lines

-

the difference between instantaneous impedance; input impedance; odd/even mode impedance; and characteristic impedance

-

microstrip vs stripline geometry and what are the first and second order effects on impedance

-

single-ended vs differential transmission lines

-

reflections when instantaneous impedance changes

-

terminating transmission line circuits

-

the physics of crosstalk and mitigation techniques

-

return and displacement currents and their roles in transmission lines

-

what every scope user needs to know about transmission lines

-

and more……

Furthermore, Eric also blends in actual practical time domain reflectometry (TDR) measurement experiments as well as SPICE circuit models with open sourced Quite Universal Circuit Simulator (QUCS) software. He provides links to the software and most importantly, he provides the actual QUCS circuit files he used in his video tutorials so you can play around with them yourself. This greatly accelerates your learning curve.

As a signal integrity practitioner, I’m used to thinking and analysing transmission lines in the time domain. One of the things I finally understood by reading the book is how to analyze transmission lines in the frequency domain. That’s when I experienced the ah-ha moment and realized that I could simply determine the characteristic impedance of a transmission line if I followed the 2-port shunt VNA measurement technique, popular in the PI world.

I’m sure you can scour the internet and search for similar content, but why would you want to, when everything you practically wanted to know about transmission lines, you can get in one reference book. It has something for everyone, whether a young engineer starting out, or seasoned grey-hairs, like me. I wished I had this book 25 years ago when I began my journey with signal integrity.

So to answer Eric’s original question, “Do we really need another transmission line book?” Well, after reading the book, I would confidently say, “Yes!”

COUPLED TRANSMISSION LINES AND CROSSTALK

Originally published Signal Integrity Journal August 9, 2022

When two coplanar parallel traces running in close proximity over the coupled length, as shown in Figure 1, they are electromagnetically coupled together.

When two complementary signals are transmitted, there is mutual electromagnetic coupling defined by the amount of mutual inductance and capacitance. This is known as differential signaling. The differential impedance (Zdiff), is the instantaneous impedance of a pair of transmission lines.

The impedance of each trace, when driven differentially, is known as the odd-mode impedance (Zodd). Conversely, when each trace is driven with the same polarity, the impedance of each trace is known as the even-mode impedance (Zev).

Differential impedance is simply twice the odd-mode impedance:

Equation 1

When Zodd = Zev, the traces are deemed to be uncoupled and there will be no crosstalk (XTalk). The characteristic impedance (Zo) of a single trace, in isolation, is equal to the geometric average (Zavg) of Zodd and Zev. When Zodd and Zev are not equal, there will be some level of XTalk, depending on the space between traces. In this case, Zo is approximately equal to Zav and is given as;

Equation 2

Crosstalk

There are two types of XTalk generated; Near-End (NEXT), or backwards XTalk, and Far-End (FEXT), or forward XTalk.

Figure 1 Illustration of NEXT and FEXT. As the aggressor signal propagates from port 3 to port 4, Near-End XTalk appears on port 1 and Far-End XTalk appears on port 2 after one time delay (TD) of the interconnect.

NEXT

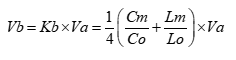

Refer to Figure 1. Through electromagnetic coupling, NEXT voltage (Vb) is related to the coupled current through a terminating resistor (not shown) at port 1; when driven by an aggressor voltage (Va) at port 3. When port 1 is terminated, the backward crosstalk coefficient (Kb) is defined by;

Equation 3

where;

Vb = the voltage at port 1

Va = the peak voltage of the aggressor at port 3

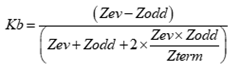

The general signature of the NEXT waveform, for a gaussian step aggressor, is shown in Figure 2. Va is the aggressor voltage at port 3 of Figure 1. Vb is the NEXT voltage at port 1. The NEXT voltage continues to increase in response to the rising edge of the aggressor until it saturates after the aggressor’s rise-time. The green waveform (VaFE) is the aggressor voltage at port 4 after one time delay (TD). The duration of Vb waveform lasts for 2TD of the coupled length.

Figure 2 NEXT voltage signature, Vb in response to a gaussian step aggressor, Va. The duration of NEXT is equal to 2TD of the coupled length. VaFE is the aggressor voltage shown after one TD. simulated with Teledyne Lecroy WavePulser 40iX software.

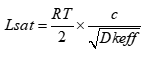

When TD is equal to one-half of the linear risetime, the NEXT voltage becomes saturated. The minimum length to reach saturation is known as the saturated length (Lsat), and is given by [1]:

Equation 4

where:

Lsat = the saturation length for near-end cross talk in inches

RT = Linear risetime to reach Va in ns

c = the speed of light = 11.8 in nsec

Dkeff = The effective dielectric constant surrounding the trace.

For example, a signal with a linear RT of 0.1nsec, to reach an aggressor voltage of 1V using FR4 material, with a Dkeff of 4, the saturation length in stripline is;

Important note: In PCB stripline construction, Dkeff is the Dk of the dielectric mixture of core and prepreg. But in microstrip, without solder mask, Dkeff is the mixture of Dk of air and Dk of the substrate. It is very difficult to predict the exact Dkeff in microstrip without a field solver, but a good approximation can be obtained by [3];

Equation 5

where;

DkeffMS = effective dielectric constant surrounding the trace in microstrip

Dk = Dielectric constant of the material

H = Height of dielectric

W = trace width

t = trace thickness

For example, a signal with a linear RT of 0.1ns, to reach an aggressor voltage of 1V and DkeffMS of 2.64, the saturation length in microstrip is;

If the coupled length (Lcoupled) is less than Lsat, the NEXT voltage will peak at a value less than the saturated NEXT voltage. The actual NEXT voltage, Vb is scaled by the ratio of coupled length to saturation length and is given by [1]:

Equation 6

For example, for a coupled of length of 100 mils and saturated length of 295 mils, NEXT voltage will be (100/295) or 33.9% of the saturated NEXT voltage.

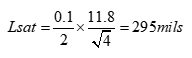

NEXT vs Coupled Length in Stripline

Figure 3 plots NEXT voltage vs coupled lengths for 100mils, 295 mils and 590 mils representing less than, equal to and greater than Lsat respectively. For a coupled stripline geometry modeled with Polar SI9000 field solver (Figure 3B), Kb is 0.065.

Each length was then simulated in Polar Si9000 and touchstone files were imported into Keysight PathWave ADS software for further analysis. The results are plotted in Figure 3A.

Figure 3 Example of NEXT voltage vs couple lengths of 100 mils, 295 mils and 590 mils in stripline, with linear rise time of 0.1ns. Modeled with Polar Si9000 and simulated with Keysight PathWave ADS.

As can be seen, using a 1V aggressor with a linear risetime of 0.1ns and a saturated length of 295 mils, the NEXT voltage is 63.2 mV, compared to full saturated NEXT voltage of 64.8 mV. With a coupled length of 100 mils, NEXT voltage saturates at 22.2 mV, for the duration of the aggressor’s risetime, compared to 22.03mV predicted by Equation 6 [1].

NEXT vs Coupled Length in Microstrip

Similarly, Figure 4 plots NEXT voltage vs coupled lengths for 100mils, 363 mils and 590 mils for Lsat respectively. For a coupled microstrip geometry modeled with Polar SI9000 field solver (Figure 3B), Kb is 0.055.

Each length was then simulated in Polar Si9000 and touchstone files were imported into Keysight PathWave ADS software for further analysis. The results are plotted in Figure 4A.

Figure 4 Example of NEXT voltage vs couple lengths of 100 mils, 363 mils and 590 mils in microstrip with linear rise time of 0.1ns. Modeled with Polar Si9000 and simulated with Keysight PathWave ADS.

As can be seen, using a 1V aggressor with a linear risetime of 0.1ns and a saturated length of 363 mils, the NEXT voltage is 54.6 mV, compared to full saturated NEXT voltage of 54.9 mV. With a coupled length of 100 mils, NEXT voltage saturates at 15.8 mV for the duration of the aggressor’s risetime, compared to 15.1mV predicted by Equation 6.

The magnitude of the NEXT voltage is a function of the coupled spacing between the two traces. As the two traces are brought closer together, the mutual capacitance and inductance increases and thus the NEXT voltage, Vb, will increase as defined by [1];

Equation 7

where;

Vb = NEXT voltage on victim

Kb = Backward crosstalk (NEXT) coefficient

Va = Aggressor voltage

Cm = Mutual capacitance per unit length

Lm = Mutual inductance per unit length

Co = Trace capacitance per unit length

Lo = Trace inductance per unit length

Unfortunately, the only practical way to calculate Kb is to use a 2D field solver to get the inductive and capacitance matrix elements from a field solver.

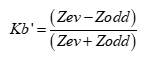

Alternatively, if only the odd and even mode impedances are known, then Kb is given as [2];

Equation 8

where;

Zterm = Victim input termination impedance, normally the characteristic impedance (Zo) of a single trace.

When Zterm is open circuit, Kb’ is given as [2];

Equation 9

FEXT:

FEXT voltage is correlated to the coupled current through a terminating resistor (not shown) at port 2 of Figure 1. The forward crosstalk coefficient, Kf, is equal to the ratio of FEXT voltage to aggressor voltage at the far end, defined as;

Equation 10

where;

Vf = the far end crosstalk voltage

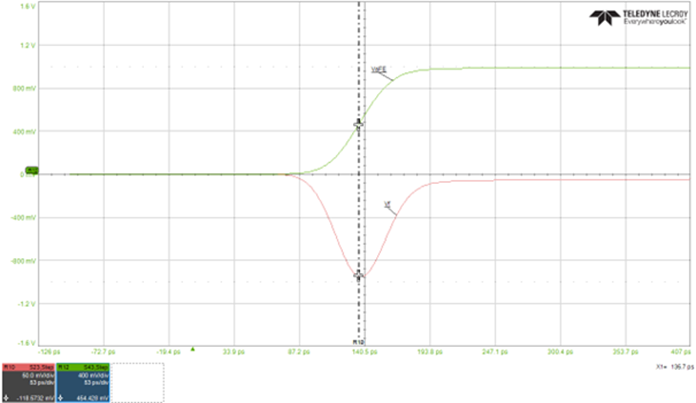

VaFE = the peak voltage of the aggressor at far-end

The general signature of the FEXT waveform, for a gaussian step aggressor, is shown in Figure 5. Vf is the forward crosstalk voltage at port 2 of Figure 1. VaFE is the aggressor voltage appearing at the far end port 4. FEXT voltage differs from NEXT in that it only appears as a pulse at TD after the signal is launched. In this example, the negative going FEXT pulse is the derivative of the aggressor’s rising edge at TD. The opposite is true on the falling edge of an aggressor.

Figure 5 FEXT voltage signature, Vf, is forward crosstalk (FEXT) voltage in response to a gaussian step aggressor voltage, VaFE. Simulated with Teledyne Lecroy WavePulser 40iX software.

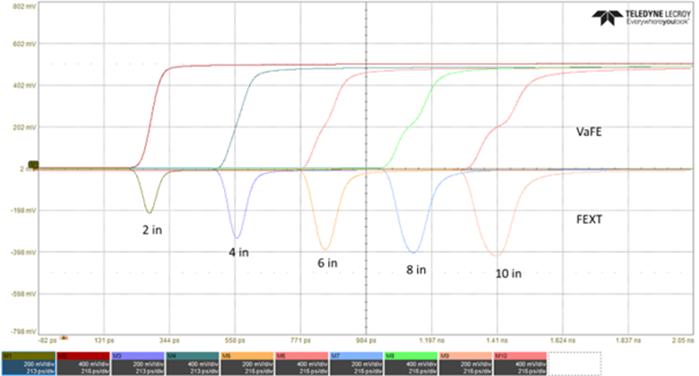

Unlike the NEXT voltage, the peak value of FEXT voltage scales with the coupled length. It peaks when its amplitude grows to a level comparable to the voltage at 50% of the aggressor’s risetime at TD as shown in Figure 6. In this example, the coupled lengths are: 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 inches respectively.

As the wave propagates along the transmission line, the RT degrades due to the dielectric dispersive loss. In the same way the aggressor waveform couples FEXT voltage onto the victim, FEXT voltage also couples noise back onto the aggressor affecting the risetime as shown. Due to superposition, the aggressor waveform shown at each TD is the sum of the FEXT voltage and the original transmitted waveform that would have appeared at TD with no coupling.

Figure 6 Microstrip FEXT voltage increase vs TD for coupled lengths of 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 inches respectively. Simulated with Teledyne Lecroy WavePulser 40iX software.

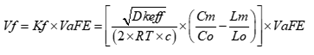

If the rise-time at TD is known, the FEXT voltage, Vf can be predicted by [1];

Equation 11

where;

Vf = FEXT voltage on victim

VaFE = Far-end aggressor voltage

Kf = FEXT coefficient

Cm = Mutual capacitance per unit length

Lm = Mutual inductance per unit length

Co = Trace capacitance per unit

Lo = Trace inductance per unit length

RT = Risetime of aggressor signal at TD in sec

c = Speed of light

Dkeff = Effective dielectric constant surrounding the trace

Len = Length of trace

Although the inductive and capacitive matrix elements can be obtained using a 2D field solver, the rise-time is more difficult to predict because of risetime degradation, as well as impedance variations along the line causing reflections. But worst of all, as seen in Figure 6, is the forward crosstalk coupling affecting the aggressor’s risetime makes it next to impossible to predict.

The only practical way to calculate Kf is to model and simulate the topology using a circuit simulator that supports coupled transmission lines. The circuit simulator should have an integrated 2D field solver built in to allow automatic generation of a coupled transmission line model from the cross-sectional information.

Since the dielectric surrounding the traces in stripline is more homogeneous, than it is in microstrip, the best way to significantly reduce, or eliminate FEXT, is to route the traces in stripline geometry. Depending on the difference in Dk between core and prepreg used in the stackup, there is always a probability there will be some small amount of FEXT generated. The best way to mitigate this is to choose cores and prepregs to have similar values of Dk when designing the stackup.

References:

[1] E. Bogatin, “Signal Integrity Simplified”, 2nd edition, Prentice Hall PTR, 2010

[2] B. Young, “Digital Signal Integrity”, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001

[3] E. O. Hammerstad, “Equations for Microstrip Circuit Design,” 1975 5th European Microwave Conference, 1975, pp. 268-272, doi: 10.1109/EUMA.1975.332206.

[4] E. Bogatin, B. Simonovich, “Dramatic Noise Reduction using Guard Traces with Optimized Shorting Vias”, DesignCon 2013, Santa Clara, CA, USA

Field Solver Nuances: How to avoid GIGO

To avoid “garbage in, garbage out” (GIGO) with any field solver, first you need to understand the little nuances of PCB fabrication process and how to interpret manufacturers’ data sheets. But most importantly you need to understand the tool’s user interface and what it is asking for.

All 2D or 3D field solvers will give accurate impedance predictions. The differences are the type of solvers used under the hood and complexity of the user interface. Simple 2D field solvers, used in many of today’s stackup planners, simply give predicted characteristic impedance based on material properties and trace geometries. More complex, 2.5D or 3D field solvers, allow for additional material parameters and can predict insertion loss, phase delay and impedance over frequency. Some will even export RLGC and touchstone files for further signal integrity analysis.

Standard PCBs are fabricated using cores and prepreg material. Prepreg sheets are a mixture of fiberglass (glass) cloth and resin which is partially cured. Cores are simply cured prepreg sheets with copper bonded to one or both sides of the laminate. Copper is etched away on each side of the foil to leave the circuit pattern.

In a multi-layer PCB, cores and prepreg sheets are alternately stacked symmetrically above and below the middle of the layup then pressed under heat and pressure. The prepreg layers gets thinner when pressed allowing the resin to fill the voids between the copper features that were etched away on the cores.

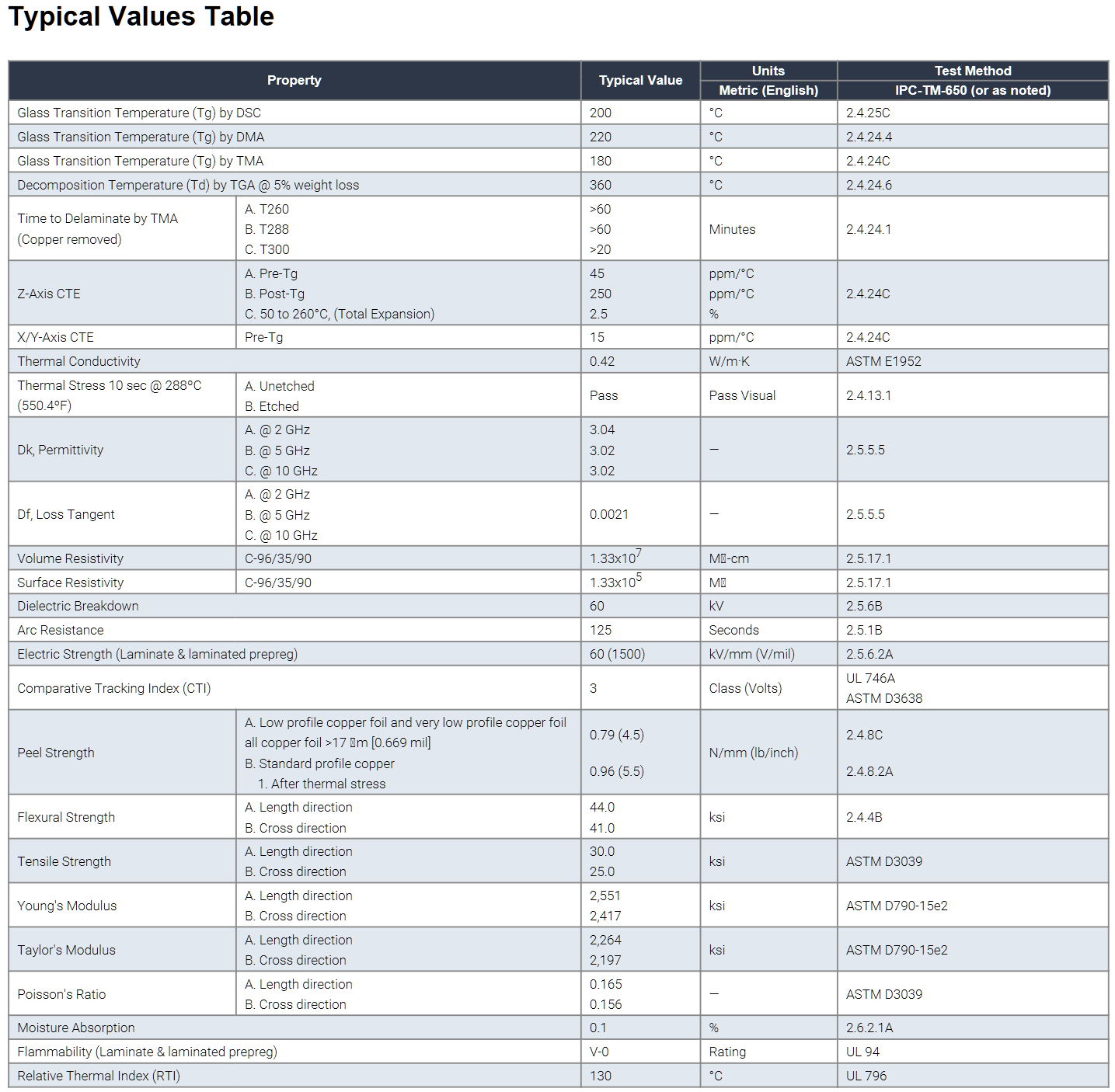

One important parameter for accurate impedance modeling is dielectric constant (Dk). The best source is from laminate suppliers’ data sheets. But all data sheets from laminate suppliers are not the same.

“Marketing” data sheets are data sheets easily found on laminate suppliers’ websites. They are meant for quick comparison of dielectric properties to narrow your search for the right laminate for your application. They include mostly thermal and mechanical properties, which are important for the physical structure of the material and how it will perform with other material properties in the stackup during processing [3].

Marketing data sheets usually only report a typical Dk value at fifty percent resin content at two or three frequency points. Depending on glass style, resin content and thickness, Dk and dissipation factor (Df), will be different for different cores and prepreg thicknesses for the same laminate chemistry. In the end, they are not representative of what is needed to design an actual stackup, or to do impedance and loss modeling. Using these numbers will almost always lead to inaccurate impedance and signal integrity (SI) results.

Instead, you need to use the same Dk/Df construction table data sheets PCB fabricators use for the stackup. Dk/Df construction tables provide the actual core and prepreg thicknesses, resin content, and Dk/Df for the different glass styles, over different frequencies. Depending on the stackup, a combination of thicknesses is often needed to meet impedance requirements and have different Dk values.

Many engineers assume Dk published is the intrinsic property of the material. But in fact, it is the effective Dk (Dkeff) measured by a specific industry standard test method. It does not guarantee the values directly correspond to design applications. When compared against measurements from a design application, there is often a discrepancy in Dkeff due to increased phase delay caused by surface roughness [1].

Dkeff is highly dependent on the test apparatus and conditions of how it is measured. One popular test method, IPC-TM-650 2.5.5.5C clamped stripline resonator test method, assures consistency of product during fabrication. Due to the nature of this test method, the materials under test are not physically bonded together, air is entrapped between the various layers. These small air gaps are caused by: roughness of the copper foil plates in the fixture; roughness profile imprint left on the surface from the foil that was removed from the test samples; copper removed on the resonant element pattern card. Air entrapment results in a lower Dkeff than what is measured because in a real PCB everything is bonded together, with no air entrapment [3].

All glass weave reinforced laminates are anisotropic, which means E-field orientation, relative to the glass weave, is different depending on test method. E-fields produced from tests like IPC-TM-650 2.5.5.5C are transverse to the glass weave and Dkeff measured is out-of-plane.

E-fields produced by TM-650-2.5.5.13 split post cavity resonators, are parallel to the fiberglass weave Dkeff measured this way is in-plane. Dkeff is typically higher for in-plane measurements, compared to out-of-plane, depending on the glass resin mixtures used in the stackup.

Another source of discrepancy is not accounting for increased Dkeff due to the pressed thickness of prepreg. Since prepreg sheets have a certain percentage of resin content for the thickness, after pressing the resin content is reduced and since Dk is a function of resin and glass mixture, there will be a higher percentage of glass after pressing and thus slightly higher Dkeff.

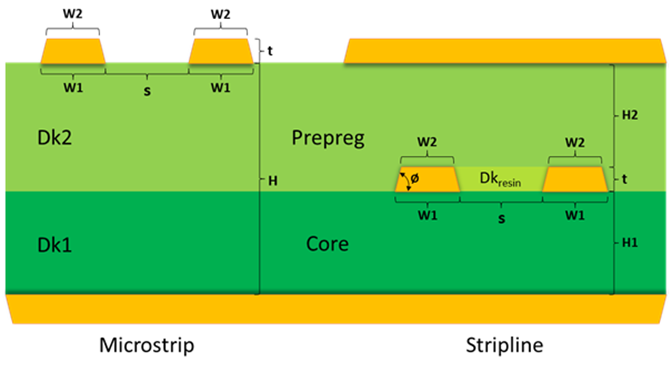

The most common PCB trace geometries are micro-strip and stripline. A simple microstriip geometry is bare copper traces over a reference plane, separated by a dielectric height H, as shown in Figure 1. Depending on the stackup, there may be a core and prepreg layer between the outer layer and reference plane with the same or different Dk values for Dk1 and Dk2.

Simple stripline geometry has copper traces between two reference planes. For single-ended (SE) signals, there is only one trace used in the field solver to calculate the SE impedance. For differential pairs, there are two traces separated by a space. Because resin fills the voids between copper features the Dkresin will be lower than Dk1 or Dk2, shown in Figure 1.

The last thing to note is the wider side of the trace always faces the core material. This is a very important point to remember when using any field solver. If you get it reversed, it will lead to inaccurate results.

Figure 1 Generic microstrip and stripline geometries.

Thickness of copper traces is an important parameter for accurate impedance prediction. Copper thickness is usually specified in ounces per square foot. Most common thicknesses for inner layer traces are ½ oz. and 1 oz. foil. But field solvers expect an actual thickness dimension.

Most designers assume 0.7 mils (18um) thickness and 1.4 mils (36um) for ½ oz. and 1 oz. respectively. But because of the price of copper, the copper you get from foil manufacturers will likely be the minimum thickness allowed under IPC-4562A. When you factor in the typical thickness after fabrication, the typical thickness can be 0.6 mils (15um) and 1.2 mils (30um). But the minimum thickness allowed under IPC-A-600G-3.2.4 is 0.45 mils (11.4um) and 0.98 mils (24.9 um) for ½ oz. and 1 oz. respectively.

Due to the nature of the etching process, the traces will usually be trapezoidal in shape. This is known as the etch factor (EF), as defined by IPC-A-600G. It is the ratio of the thickness (t) to half the difference between W1 and W2.

Thus,

Some field solvers will define EF differently so it is important to understand how to specify it properly.

Once you’ve come up with a proposed stackup, the next step is to do some impedance modeling. Normally your fab shop comes up with this, but it is a good idea to validate their proposal, to ensure you are in sync with them.

The first thing to do, is identify the layers from which to model. Next, is to use your field solver, to model characteristic impedance. Since all field solvers are different, and user interfaces can be confusing, make sure you understand the little nuances of your tool.

The next thing is to identify the core layers in the stackup and input H1 and Dk1 for the dielectric. Then, input the pressed thickness for prepreg H2 and Dk2, not the thickness found in Dk/Df construction tables. You can usually trust the pressed thickness from your fab shop. But be careful how the field solver defines H2. Most field solvers define it as shown in Figure 1, but some solvers, like Polar Si9000e, define it as (H2+t), shown in Figure 2. Usually, you can trust the pressed thickness from your board shop stackup drawing.

Finally, if your field solver allows for it, fill in Dkresin between two traces if you know it. It will be lower than Dk2. Since this number is generally hard to obtain, a rough estimate to use is the lowest Dk value from the highest resin content prepreg found in Dk/Df construction tables.

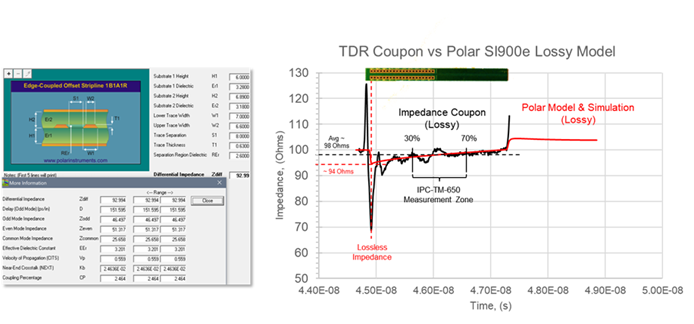

Once everything is set up, optimize the line width and space, until the desired characteristic impedance is reached. One last point to remember, is that all 2D field solvers only calculate lossless characteristic impedance. But when we measure an impedance test coupon with a time domain reflectometer (TDR), we are measuring the instantaneous impedance along the PCB trace.

More often than not, impedance is different than what was predicted. This is because a 2D field solver only calculates the lossless characteristic impedance of the cross-sectional geometry; while a TDR measures the instantaneous impedance of a lossy transmission line at every point along its length.

A 2D field solver has no input for conductor resistivity, dielectric loss, or how long the conductor is. Resistive loss often results in a slow monotonic rise in the impedance profile. IPC-TM-650 specifies the measurement zone between 30-70 % and most PCB fab shops, will measure an average impedance

In this example, shown in Figure 2, for a low loss dielectric, there is a 4-5 ohm difference depending on where the measurement is taken. When all input parameters are included correctly for a lossy transmission line model, you can see there is excellent correlation.

Figure 2 Lossless characteristic impedance from Polar SI9000 field solver (left) vs measured TDR plot from an impedance coupon and lossy transmission line model from Polar Si9000.

Although minor differences in individual parameters may have second order affects, collectively they could add up to give poor correlation to measurements. But if you consider all the nuances discussed in this article, you can get pretty good accuracy as shown in Figure 2.

[1] Bert Simonovich, “A Practical Method to Model Effective Permittivity and Phase Delay Due to Conductor Surface Roughness”, DesignCon 2017, Santa Clara, CA

[2] Bert Simonovich, “PCB Fabrication: What SI/PI Engineers Need to Know for First Time Modeling Success”, DesignCon 2021 Spring Break Webinar, April 12, 2021

[3] Bert Simonovich, A Tale of Two Data Sheets and How Foil Roughness Affects Dk, White paper

A Tale of Two Data Sheets Part 2: Making Sense of “Design” Dk

Originally published in Signal Integrity Journal, May 31, 2022

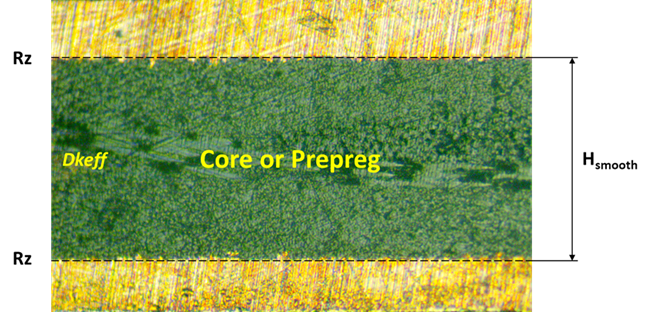

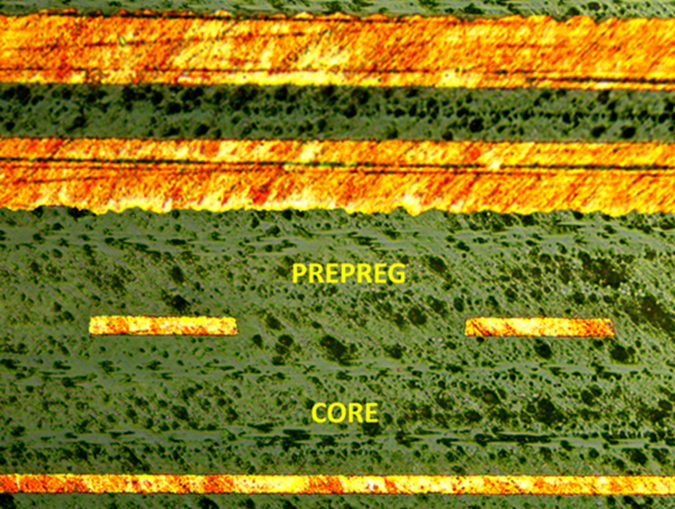

In part one, “A Tale of Two Data Sheets”, I explained how air entrapment, due to IPC-TM-650-2.5.5.5 test method manual [7], is the primary reason for effective dielectric constant (Dkeff) and phase delay discrepancies between simulation and device under test (DUT) measurements. Entrapped air of the test fixture results in a lower Dk published in laminate suppliers’ Dk/Df tables than what would be measured in a real printed circuit board (PCB) application. This is because in a real PCB, everything is bonded together with no air entrapment, as shown in a cross-section view of Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of foil bonded to core or prepreg dielectric. Rz is 10-point mean roughness of foil as measured by a profilometer. Hsmooth is the thickness of the dielectric as if the foil was removed.

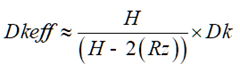

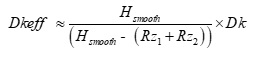

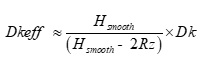

When copper foil with the same Rz roughness is bonded to each side of the core or prepeg, Dkeff is determined heuristically from published Dk by this simple correction factor [1]:

Equation 1.

where:

Hsmooth is the thickness of the dielectric as if the foil was removed

Dk = Dielectric constant published in laminate suppliers’ Dk/Df tables

Rz = 10-point mean equivalent to Rz(JIS) or Rz(DIN) published in foil suppliers’ data sheets. This is not to be confused with Rq, which is RMS value of roughness.

Rogers Corporation [4] understands this. That’s why they provide the “design” Dk in addition to their bulk Dk, as measured by TM650 clamped stripline resonator test method [7]. Design Dk is an average number using a differential phase length method from several different tested lots of material and on the most common thickness. This method is based on measuring phase difference from two identical microstrip transmission line geometries, of different lengths on the same panel. Because this is a real microstrip application, the dielectric is fully bonded to the copper and there is no air entrapment. Knowing the phase and length difference, the effective Dk is empirically determined.

The accuracy of the resultant effective Dk depends on several factors like:

-

-

fixture design

-

-

-

length ratio between two transmission lines

-

-

-

material thickness of the sample under test

-

-

-

the thickness of the copper

-

-

-

actual roughness of the foil on the microstrip circuit.

-

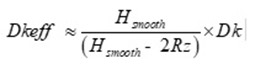

In lieu of actual Dk/Df tables, Rogers provides a handy impedance calculator as shown in in the RO4003C example of Figure 2. There are three Dk options available to use:

-

-

Z-axis bulk Dk

-

-

-

Dk values for specific frequencies

-

-

-

Dk values for characteristic impedance

-

The first radio button, as shown in Figure 2, gives the z-axis bulk Dk value of 3.55, as measured by TM650 2.5.5.5 test method manual. However, the value does not change when different frequencies are selected. This makes the number suspect since clearly design Dk does change over frequency. Thus this number can be considered equivalent to marketing data sheets, and should not be used.

When the middle radio button is selected, a Dk value for a specific frequency is displayed, which corresponds to a frequency entered in the lower right frequency box of Figure 2. This is the most useful option, since it allows the user to choose the right design Dk at whatever frequency they choose for their application, including characteristic impedance. This option already factors in the foil roughness effect, so no correction factor is needed to use in your simulator.

The last radio button selects a Dk for characteristic impedance calculation. It is a “design” Dk with yet a different Dk. Similar to the Bulk Dk option, it does not change over frequency. For any simulation tool other than the Rogers’s calculator, Bulk Dk and Dk values for characteristic impedance values should not be used.

Figure 2. Example of Rogers Corporation impedance calculator. For an 8-mil thick RO4003C dielectric, bulk Dk is 3.55 while design Dk over frequency is shown in bottom left window.

Under the information tab, the user can download design Dk over frequency, for a specified thickness, shown in the bottom left window of Figure 2. This data can be selected and copied to the clipboard and pasted into a spreadsheet for further processing.

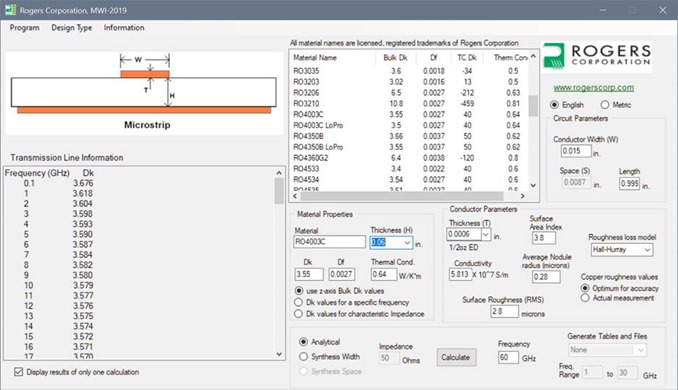

Figure 3 plots design Dk vs. frequency for various thickness from 8 mils to 60 mils for RO4003C material. As can be seen, design Dk is not constant over frequency and furthermore it is different for different thicknesses, mainly due to the roughness of the foil that is already included in the measurement.

Thinner materials have a higher design Dk than thicker materials for the same roughness of foil. This is because when the foil teeth protrude into a thin dielectric material, there is a higher concentration of e-fields, resulting in higher capacitance between top and bottom copper layers. For thick dielectrics the foil teeth have less of an impact on capacitance and thus Dkeff, as described mathematically by Equation 1.

Since the roughness of the foil does not significantly influence the design Dk for thick laminates, we can assume the bulk Dk is roughly equivalent to design Dk over frequency for the 60-mil laminate.

Figure 3. Design Dk vs. frequency for various thickness of RO4003C from 8 mils to 60 mils mainly due to the roughness of the foil. Thinner material has a higher design Dk than thicker material, for the same roughness of foil.

Heuristically, we can rearrange Equation 1 and estimate the Rz roughness of the foil used on RO4003C laminate to be 6.302 μm from Equation 2.

Equation 2.

where:

Hsmooth is the thickness of the 8 mil (203 μm) laminate

DkBulk = 3.55 at 60 GHz for 60 mil (1524 μm) laminate

Dkeff = design Dk of 8 mil (203 μm) laminate at 60 GHz

A cross-section sample from a time domain reflectometry (TDR) demo board, courtesy of Picotest [6], was measured and is shown in Figure 4. The TDR demo board was fabricated with 8-mil thick Rogers RO4003C core laminate and cladded with 2 Oz copper foil.

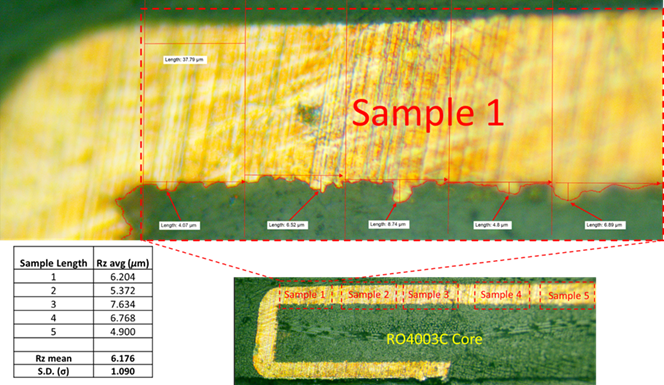

Five highlighted random sample lengths of copper roughness, labeled Sample 1 to Sample 5 of Figure 4, were analyzed. The total length of each respective sample was then partitioned into five equal sections, similar to the blow-up picture of Sample 1, to measure the maximum peak to valley height of each section. The five measurements of each sample length were then averaged to determine the Rz roughness, as described under IPC TM650 2.2.17A [8] and shown in the table of Figure 4.

The mean value of Rz for the five samples was 6.176 μm with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.090 μm. This compares favorably with the estimated roughness of 6.302 μm, determined from Equation 2.

Figure 4. A cross-section sample from a Rogers RO4003C based TDR demo board, courtesy of Picotest [6], used to determine Rz roughness of the foil.

When we use the actual roughness measured from Figure 4 and Equation 1, we can then calculate Dkeff at 60 GHz for different thicknesses, shown in Table 1. As can be seen there is, less than 1% delta compared with design Dk reported from the calculator!

Table 1. Comparison of Roger’s Design Dk vs. Dkeff when simple correction factor applied to Bulk Dk at 60 GHz.

|

Height |

Height |

Bulk Dk |

Design Dk |

Rz |

Dkeff |

Delta |

|

8.0 |

203 |

3.550 |

3.785 |

6.176 |

3.780 |

-0.13% |

|

12.0 |

304 |

3.550 |

3.702 |

6.176 |

3.700 |

-0.04% |

|

16.0 |

406 |

3.550 |

3.657 |

6.176 |

3.661 |

0.12% |

|

20.0 |

508 |

3.550 |

3.625 |

6.176 |

3.638 |

0.37% |

|

32.0 |

812 |

3.550 |

3.580 |

6.176 |

3.605 |

0.69% |

|

60.0 |

1524 |

3.550 |

3.550 |

6.176 |

3.579 |

0.82% |

Rogers Corporation provides a handy calculator in lieu of Dk/Df tables in which “design” Dk values over frequency can be used directly without correcting for roughness. When an actual cross-section was analyzed, there was excellent correlation from corrected Dkeff using heuristic methods compared to design Dk from the calculator. Therefore, “design” Dk should be used for impedance modeling and PCB stackup design when using Rogers laminates.

References:

-

-

B. Simonovich, “A Tale of Two Data Sheets and What You Need to Know About Dielectric Constant (DK),” Signal Integrity Journal article, April 2022.

-

-

-

L. Simonovich, “A Practical Method to Model Effective Permittivity and Phase Delay Due to Conductor Surface Roughness,” DesignCon 2017, Santa Clara, USA.

-

-

-

Isola Group, 6565 West Frye, Chandler, AZ 85226.

-

-

-

Rogers Corporation, 2225 W. Chandler Blvd., Chandler, AZ 85224.

-

-

-

J. Coonrod, “Managing PCB Materials: Dielectric Constant (Dk)”, Rogers Corporation, Blog Article, Sep 11, 2018.

-

-

-

Picotest, Phoenix, AZ 85085.

-

-

-

IPC-TM-650, 2.2.17A, Test Methods Manual, “Surface Roughness and Profile of Metallic Foils (Contacting Stylus Technique).”

-

-

-

Bereskin, A. B. “Microwave Dielectric Property Measurements”, Microwave Journal, vol. 35, no.7, pp. 98 – 112.

-

A Tale of Two Data Sheets: Part1

Originally published SI Journal April 26, 2022

When doing printed circuit board (PCB) stackup and signal integrity (SI) impedance modeling, we need to get the dielectric material properties from the right sources. One important parameter for accurate impedance modeling is relative permittivity (εr) of the dielectric material, otherwise known as dielectric constant (Dk). The best source is from laminate suppliers’ data sheets. Though there is an issue with these I like to think of as, “a tale of two data sheets.”

Marketing data sheets, like the example shown in Figure 1 [6], are easily found on laminate suppliers’ websites. They are meant for quick comparison of dielectric properties to narrow your search for the right laminate for your application. Dielectric properties on marketing data sheets include mostly thermal and mechanical properties, which are important for the physical structure of the material and how it will perform with other material properties in the stackup during processing.

But marketing data sheets are not representative of what is needed to design an actual stackup, or to do impedance and SI loss modeling. Depending on glass style, resin content, thickness, Dk, and dissipation factor (Df) will be different for different cores and prepreg thicknesses for the same laminate. Marketing data sheets usually only report a typical Dk/Df at fifty percent resin content and two or three frequency points. Thickness is not specified. Furthermore, Dk and Df are not constant over frequency. So, using numbers from these data sheets will lead to inaccurate impedance and phase delay results.

Figure 1. Example of a “Marketing” data sheet easily obtained from laminate supplier’s web site. Source Isola Group [6].

Instead, for transmission line modeling, one needs to use the same Dk/Df table data sheets PCB fabricators use to build the stackup. An example Dk/Df table is shown in Figure 2. Dk/Df tables provide the actual core and prepreg thicknesses, resin content, and Dk/Df for the different glass styles, over different frequencies. Depending on the stackup, a combination of thicknesses is often needed to meet impedance requirements. Each thickness will have a different Dk value.

In the example of Figure 2, Dk varies from 2.92 at 10 GHz for 1080 glass style to 3.19 at 10 GHz for 2116 glass style. This represents a Dk variation of -3.3% to 5.6% when compared to a Dk of 3.02 at 10 GHz specified in Figure 1.

Figure 2. Example of a typical “Engineering” data sheet showing Dk/Df table for different glass styles and resin content over frequency. Source Isola Group [6].

Many engineers assume Dk published is the intrinsic property of the material. But, in fact, it is the effective Dk (Dkeff) measured by a specific industry standard test method. When they are compared against real measurements from a design application, there is often a discrepancy in Dkeff due to increased phase delay caused by surface roughness [1].

Dkeff is highly dependent on the test apparatus and conditions of how it is measured. One method commonly used by many laminate suppliers is the clamped stripline resonator test method, as described by IPC-TM-650 2.5.5.5, Rev C, Test Methods Manual [10].

Since all glass reinforced laminates are anisotropic, any stripline based test method, like TM-650 2.5.5.5, or Bereskin stripline test method [13], reports Dk values in which the E-fields are transverse to signal propagation. That is, if the signal propagation is in the x-y axis direction, then the Dk measured by this method is when E-fields are in the z-axis direction.

For Isola’s Dk/Df table [6], shown in Figure 2, Dk values were measured by TM-650 2.5.5.5 test method. From that data, the values for most of the constructions are calculated. Additional verification runs are performed to gather statistical data over time and validate that the calculations are reasonable and accurate.

The measurements are done under stripline conditions using a carefully designed resonant element pattern card. It is made with the same dielectric material to be tested. As shown in Figure 3, the card is sandwiched between two sheets of uncladded dielectric material under test. Then the whole structure is clamped between two large plates; each lined with copper foil and grounded. They act as reference planes for the stripline.

Figure 3. Illustration of clamped stripline resonator test method, as described by IPC-TM-650, 2.5.5.5, Rev C, Test Methods Manual [10].

This test method assures consistency of product when used in fabricated boards. It does not guarantee the values directly correspond to design applications.

Here is why:

Since the resonant element pattern card and material under test are not physically bonded together, air is entrapped between the various layers. These small air gaps are caused by the:

-

roughness of the copper foil plates in the fixture

-

roughness profile imprint left on the surface from the foil that was removed from the test samples

-

copper removed on the resonant element pattern card

Air entrapment, due to the TM-650 test method, is the primary reason for effective Dk and phase delay discrepancies between simulation using laminate suppliers’ Dk/Df tables and real measurements from a design application. The small air gaps result in a lower effective Dk than what would be measured in a real PCB because everything is pressed together with no air entrapment, as shown in a cross-section view of Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of foil bonded to core or prepreg dielectric. Rz1 is rougher than Rz2 and Hsmooth is the thickness of the dielectric as if the foil was removed.

When copper roughness is different on each side of the dielectric, like the example shown in Figure 4, Dkeff is determined heuristically by this simple correction factor:

Equation 1.

where:

-

Hsmooth is dielectric core thickness from laminate suppliers’ Dk/Df table data sheet or pressed prepreg thickness from the PCB stackup drawing.

-